by Tanya Michele Amador

Prevailing art historical discourse often briefly references the audience as being participants in an artwork, but seldom goes deeper into the individual viewer’s experience. This study proposes a new method of analysis through the use of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA). A qualitative method of data collection, IPA allows the reader to understand a chosen individual subject’s reception of a particular event, or ‘phenomena’, from their perspective and specific context(s). Using a video of a performance, Exergie Butter Dance (2000–15) by Indonesian performance artist, Melati Suryodarmo, as a case study, this ongoing research project draws from an insightful interview process with individual spectators to narrate how the viewer’s preconceived notions, cultural values, experiences, and pre-programming cause them to understand performance works in the ways that they do.

Background and framework

Existing frameworks for considering performance art tend to scrutinise the art form by addressing its ephemerality, the use of the artist’s body, and psychological nuances as pertaining to emotionally elicited affects. These structures many times ignore altogether the habitus of the spectators.

For example, the use of feminism as a framework does not typically consider the viewer’s perspective, but rather focuses on the artist’s critique of patriarchal dominance and their reclamation of the female body, using the performance as a vehicle. Art historical discourse often briefly references audience participation, but seldom goes deeper into the experience of the viewer. The same holds true with sociological and textual framing which focus on political and social themes. Granted, these frameworks give us much insight, such as an understanding of an artist’s oeuvre, the psychology of the performer, the emotions they affect, and the somatic uses of the body and their implications. However, they fail to help us understand how a spectator reads a work, why the performance causes them to receive the works in the ways that they do, and how this differs from viewer to viewer.

According to Amelia Jones in “Presence’ in Absentia”, for the spectator, a performance is a projection of a situation in which the viewer’s own desires take place. Drawing from Jacques Derrida, Jones asserts that, “body art performances exacerbate the body’s supplementarity and the role of representation in momentarily securing its meanings through visible codes signaling gender, race, and other social markers.” She goes on to argue that “the body in performance is fully dependent on the ways in which the image is contextualised and interpreted (by the viewer).” Performance art has always been a fundamentally disputed and contested genre of contemporary art. It has also remained one of the most inaccessible for spectators to understand and connect with. While an artist might be direct or ambiguous in conveying meaning to an audience, it is ultimately the viewer who determines how the work is absorbed and interpreted, or “received”.

Research methodology

The first and most important foundation of IPA is phenomenology, the very word contained in its title. Phenomenology is essentially a philosophical approach to the study of experience. The founding theory that established the phenomenological approach is Edmund Husserl’s argument for the meticulous assessment of the human experience in its intentional consciousness. Hence, the essence of this research is dedicated to applying this method of analysis to the individual’s reception of a particular event, or “phenomena” in the context of the particular chosen individuals and their specific circumstances. Further, this paper considers Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological theory that each individual’s experience in the world is unique to their own “embodied” nature.

The selection procedure of choosing sample subjects for an IPA study is far more detailed than is possible to fully delve into for the purpose of this article’s approved length, but it most commonly demands a fairly homogeneous and small group of participants for whom the research question would be meaningful. Furthermore, studies of this type aim towards theoretical transferability rather than empirical generalisability and search for connections across emergent themes by contextualising them within the personal accounts of each participant’s cultural and temporal experiences. Normally a study such as this focuses on more precise key moments in a participant’s life. However, during the interview process, the interviewees’ narratives do not always provide such specific information but on a whole, in my experience, their accounts often related to their familiarities in a broader sense of retrospection on culture within family, social and work life.

In purporting to discover the most optimal way to understand how the/an audience grasps a performance, I asked the participants the question: “what do you think?”, “What do you really think and why?” To take the thought process further: How do you receive it? What does it mean to you and why?

Case study: Melati Suryodarmo Exergie Butter Dance

Regularly placed within an international lineage, Indonesian artist Melati Suryodarmo is a pioneer of performance art in Southeast Asia. Trained in Butoh dance under the master, Anzu Furukawa, Melati has been performing internationally since 1999. Melati was also mentored by Marina Abramović and has championed performance art from the early days of her artistic development.

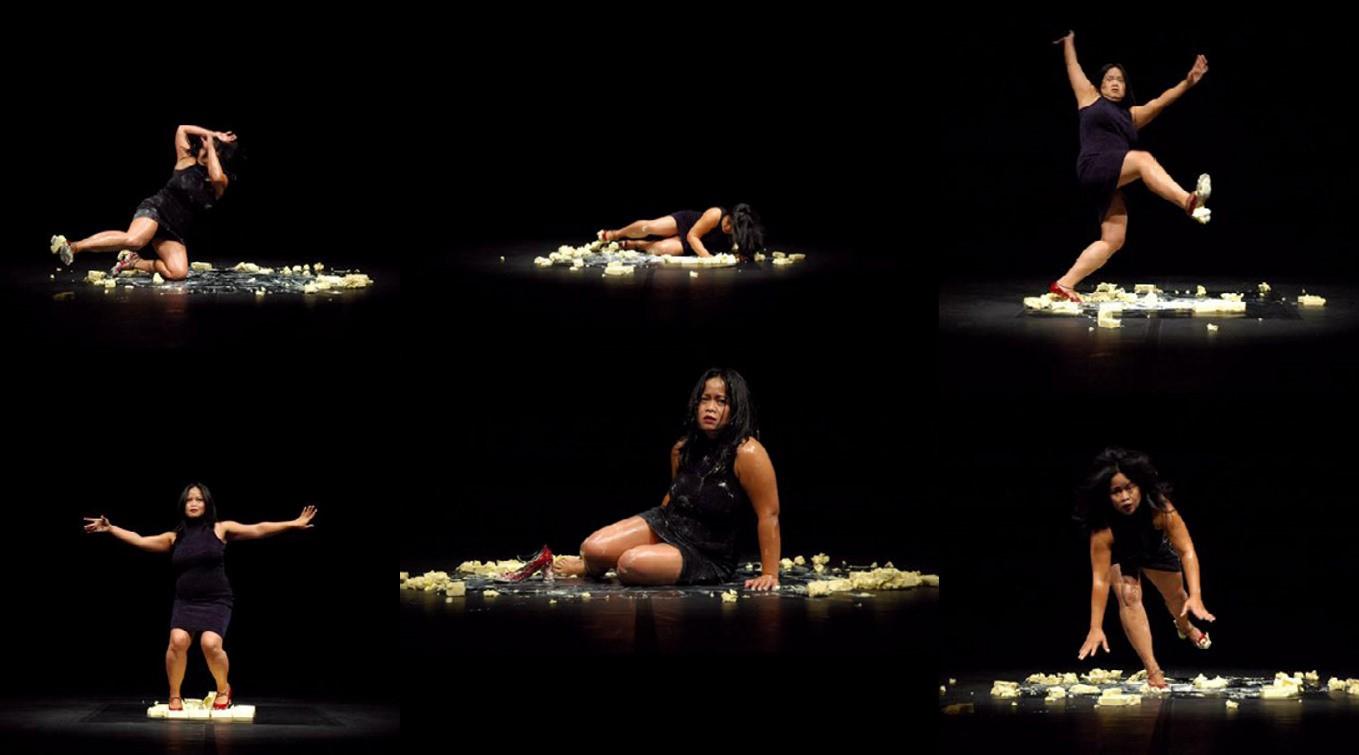

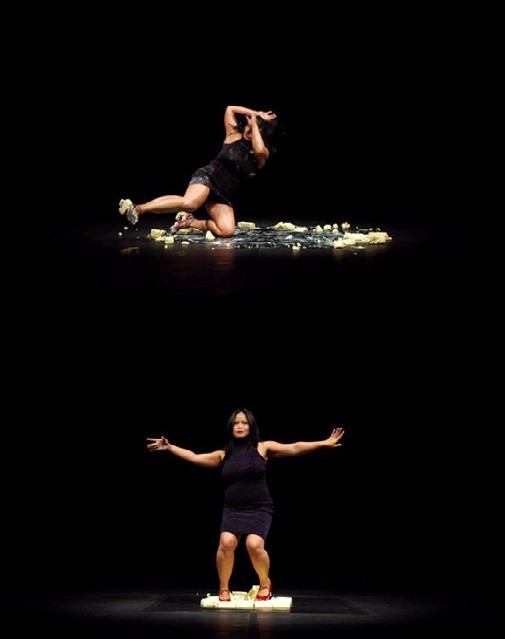

Exergie Butter Dance (Figures 2.1–2.6) is a live performance that was first presented in Berlin in 2000 and afterwards performed and screened in other cities globally. The 6:10 minute, single-channel video clip of the 20-minute performance shown to participants in my study is from an iteration Melati performed in Malmö, Sweden in 2010. Photographic and video documentation of the performance can also be found in the collection of the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) and the work was performed there as part of the group exhibition Medium at Large (2014–2015).

Melati’s performance is set against a completely dark background and black floor. She dances sensually and slowly on a pile of butter to traditional Javanese drum music, dressed in a tight black dress and red high-heeled shoes. During the performance she continually loses her balance, and with a look of terror on her face, falls down harshly and gets back up to repeat the movements, over and over, obviously suffering through much pain.

Photo courtesy of Melati Suryodarmo

At a recent workshop in October 2018 conducted as part of Da:ns Lab’s This is Women’s Work, Melati presented an account of several of her performances over the years. In this lecture, she described Butter Dance as a way of overcoming her existential fear of life and failure, the main objective being to fall and get back up again. For her, the performance embodies her displacement and her exploration of the duality of her identity that comes with being a diasporic artist.

Findings

By contextualising the participants’ narratives within the important moments of their lives that have had the most impact on their predispositions, I reached an abundance of conclusions by evaluating the emergent themes garnered from the interviews. Although each participant hails from a different cultural group, they have all lived in the diaspora. Thus, the cultural values and life experiences which stem from their Asian identities affected how they received the performance, but this was in turn influenced by worldviews influenced by their experiences of living in Western countries. These characteristics of these individuals made the group fairly homogenous.

Common themes in participants’ reactions in the study included defeat, but also perseverance, strength, courage, and acceptance, based on their own experiences and identities. This included one participant who related his experience of the performance to challenging times he has had in his career, his distant relationship with the conservative and religious values of his family because of his sexual orientation, as well as his subsequent tenacity to continually pick himself up and accept himself. Another participant related the performance to her experiences as a woman in a job in which she observed gendered trauma, stating that watching the performance took her back to the dark place of a haunting moment she would never forget. In Melati she saw the same strength of the women she observed in the sex trade.

In past critical art historical discourse of Southeast Asian art, Butter Dance has been examined within the frameworks of gender, feminism and sexuality. The focus on Melati’s attire in the performance has been sexualised consistently and these themes were echoed by the participants in this survey when they each described her attire as being sexy. One participant called the red shoes “risqué” and another likened the butter to “lubricant” used in sexual intercourse.

Photo courtesy of Melati Suryodarmo

Photo courtesy of Melati Suryodarmo

Conclusion

The primary aim of this study has been to develop a new methodology for considering audience reception of performance art on a more intrinsic level, rather than solely relying on existing methods, as most art historical discourse remains fundamentally driven by exhibitionary curatorial agendas. At present, these approaches are predominantly hypothetical as they do not emphasise subjectivity and the “embodied nature” of the individual, as per Merleau-Ponty’s theory of experience in the world. The employment of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis offers an avenue to accomplish this in the future, thus enhancing academic positioning of audience reception in art history.

Assuming that in developing this process as perhaps one of the most adequate methods for mapping how spectators receive a performance by Indonesian performance artist Melati Suryodarmo, or any performance for that matter, the secondary function of this study is, what can the data tell us about the what and how of audience reception of Butter Dance.

Concisely, all three of the participants received the performance by attributing its meaning to their own experiences of Asianness, identity, and diaspora, with empathy and admiration for Melati, with some assigning meaning to sexual identity. It also illustrates that differences in their receptions also exist, supporting Jones’ argument that the performance is “fully dependent on the ways in which the image is contextualised and interpreted [by the viewer].”

It is with optimism that I hope this framework may in future be utilised by researchers so that they can evaluate its transferability to persons who share similar contexts. While this is an investigation into an alien terrain with perhaps, lofty goals, it is undertaken with faith that further mapping might be fulfilled by myself and/ or by others in future to build a greater representation of wider populations in Southeast Asia, opening the doors to broader understanding of the reception of performance art.

Tanya Michele Amador graduated from the MA Asian Art Histories programme in 2019.

Exergie Butter Dance can be viewed here.