by Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani

Across the unraveling of the film, key cinematic spaces are used to this end, in an effort to spatialise underlying notions of cultural belonging and identity, and the grip of tradition on the rapidly evolving Vietnamese society.

Three Seasons, by Vietnamese-American film director Tony Bui, was released in the United States in 1999. Bui left Vietnam with his family at the age of two, following the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, and spent his formative years in the United States. Belonging to the significant ‘1.5 generation’, Bui was exposed, along with his contemporaries, to the way the United States viewed and represented the war in mainstream culture. That is, the war became, in its immediate aftermath, “a resource for the American culture industry”. Publishers, television reporters, film and music producers contributed to immortalising the war into a “media-myth”. Ranging from Apocalypse Now (1979) to The Deer Hunter (1978), Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and Forrest Gump (1994), to name but a few, mainstream moving images undoubtedly took centre stage in American social culture as a way to acknowledge the trauma of the war with which the American society was struggling to come to terms. In this effort, shared by the growing Vietnamese diaspora, to counterbalance the predominant American discourse on the war and, also, to learn about Vietnam, a country largely unknown and unfamiliar to the filmmaker and his diaspora, Bui’s cinematic choices have favoured, throughout his career, the depiction of a nostalgic, bygone Vietnam that would allow him to figuratively “translate notions of misery, heritage and history to a diasporic spectatorship”. To this end the Vietnam depicted in most of Bui’s production is an idyllic blend of ideals and aesthetics, where “curiosity vies with nostalgia, and reconciliation often overcomes resentment”.

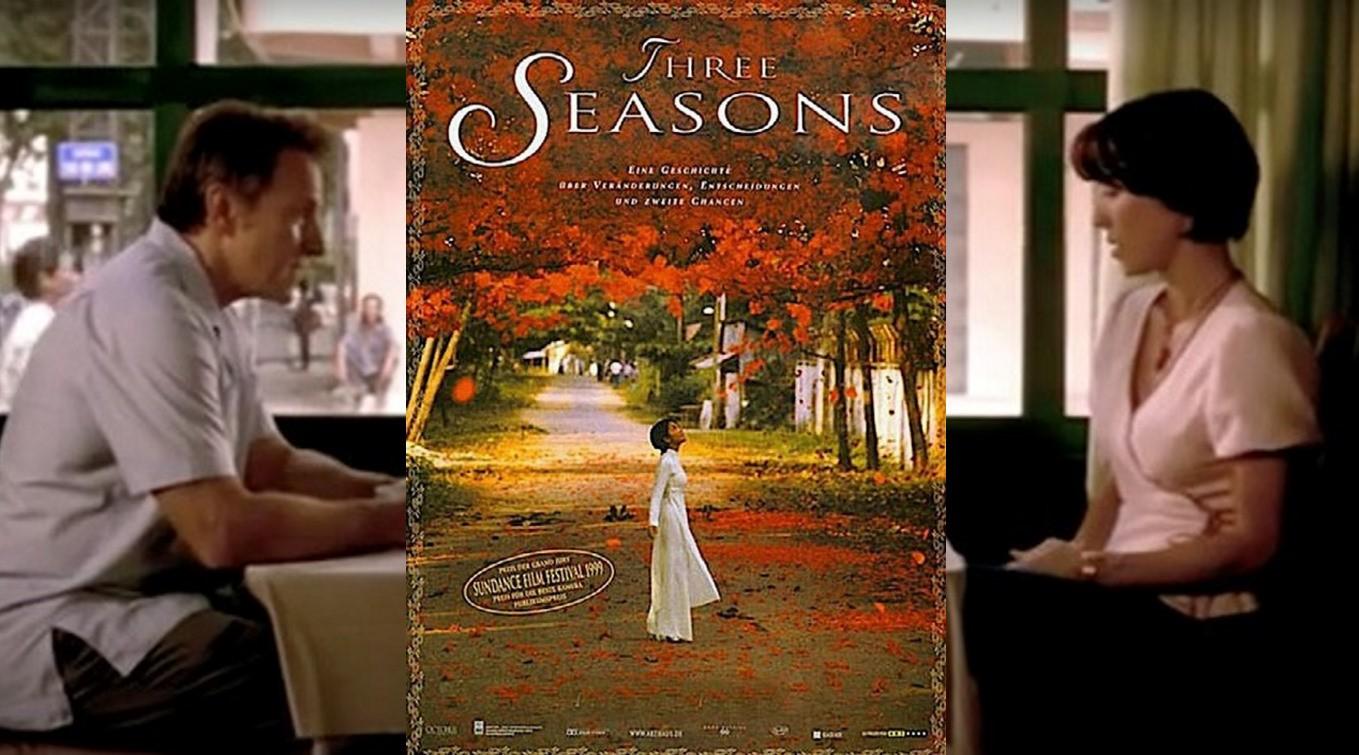

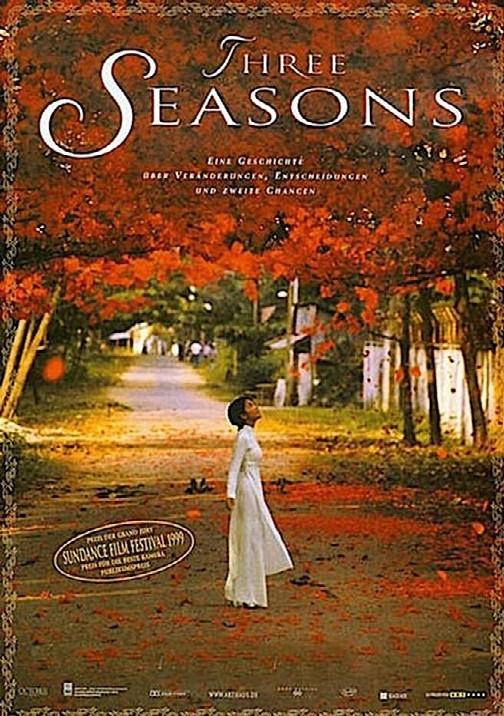

Three Seasons, Bui’s first feature film produced when he was only 26 years old, is located at the intersection of cross-cultural encounters. Despite being an effectively American production, Three Seasons was granted permission to be fully shot on Vietnamese grounds. Also, in contrast to its American counterparts, Three Seasons is shot entirely in Vietnamese, except for a few sequences in which Harvey Keith, American actor and co-executive producer of the film, appears. Notwithstanding the film’s large outreach across America and Europe, as well as its several award nominations, it received mixed responses by critics and the public and was criticised for being an “unashamedly sentimental movie” that makes use of fairy tales and stock images to tap into sugar-coated sentiments of lost virtues in the face of globalisation. Viewed in this context, the poster promoting Three Seasons, a key visual for the marketing campaign worldwide, is particularly telling. The poster depicts an artificial locale: the foreground is framed by a cascade of red petals; on both sides, trees along a quaint, rural path converge. The focal point is an “exotic” female figure wearing a white áo dài. The tagline reads: A haunting tale of changes, choices and second chances.

Beyond the visual artificiality of the film’s brand image, how does the movie actually embody the nostalgic cliché of a bygone Vietnam, which, in post-Đổi Mới 1999 (when the film was first released) was conversely encroaching on Western sentiments? In this paper, I propose that we approach the filmic narrative of Three Seasons from a spatial, or ‘architectural’, perspective to analyse the performative potential of key cinematic spaces. To do so, I focus on the use of cinematic space in Three Seasons as a discursive tool to apprehend how the conceptual deployment of contested or imagined spaces is able to contribute to the creation of a nostalgic vision of Vietnam, exoticised by American mainstream movies into a distant, oriental Other. Across the unraveling of the film, key cinematic spaces are used to this end, in an effort to spatialise underlying notions of cultural belonging and identity, and the grip of tradition on the rapidly evolving Vietnamese society. Varying from glamorous to dilapidated buildings, street alleys, private homes and temples, to cinema halls, shops and restaurants, the “represented or produced spaces” in Three Seasons, this paper argues, serve as tangible referents to a reality that is adapted to accommodate, and in response to the filmmaker’s cross-cultural outlook on Vietnam, a country Bui and his contemporaries would have known only through “American movies and books, all of them in the English language”. Specifically, this paper focuses on three distinct localities that function as the film’s visual and conceptual landmarks: the Temple, which is portrayed as the ultimate locus of tradition; the Roundabout, which functions as a transitional space; and the Hotel, highlighted in the film as a space of transaction. Together the tradition-transition- transaction association contributes to depict Vietnam as an imagined land, at once idyllic and in danger of losing its soul. In fact, the Temple, the Roundabout and the Hotel are the film’s real exponents, whose corollaries are their inhabitants: Dao, teacher and poet, and Kien An, the lotus farmer, in the temple; Hai, the cyclo driver, Woody, the street urchin, and James Hager, a former GI, in the city’s roundabout; and Lan, the redeemed prostitute, at the hotel. Discussed in the paper as a second line of inquiry are in fact the inhabitants of said spaces and their ethnographic specificity to each locale in the attempt to address underlying questions of identity and cultural belonging.

Represented or produced spaces

Take one: The Temple

The film opens with a pastoral scene over a luscious, emerald-green lotus pond. Located in the middle of a pond created by the film crew to evoke a bucolic sanctuary is the residence of Teacher Dao (Tran Manh Cuong), one of the main characters in the intertwining plots of Three Seasons. Elderly and stricken with leprosy, Teacher Dao is the only inhabitant of the residence but, precisely because it is the locus of Dao’s poetry and higher thinking, the residence is elevated to the status of spiritual shrine: a Temple, as it is referred to throughout the film. The Temple’s architectural structure resembles that of an aristocratic house with a large compound that extends into the surrounding pond by large, sheltered patios and salas. Surrounded by water and lotuses, the Temple’s floating appearance exudes a sense of mystery. This mysterious dimension is further emphasised by the Temple’s cavernous interiors. The long and detailed pan views of the interior are systematically shot in the dark, revealing only sparse, dimly lit furniture: the desk, at which Teacher Dao writes his poems; his wheelchair; and his bed, visible only at the time of his passing in the film’s final sequence. Viewed from within, the Temple is covered in dust, which, whether physical or imaginary, accumulates over objects and ideals. Viewed from the pond, the Temple seems to be reachable only by water, save for a rudimentary bridge that is a metaphor for the only link to Vietnam’s fading traditions.

As the film unfolds, sequences of modern Saigon, whose periphery the Temple inhabits, bleed abruptly into shots overlooking the Temple. From pan views of the interior and exterior, to close-ups of the pond’s white lotuses and portraits of its farmers, the site of the manufactured Temple underlines, visually and conceptually, the elegiac value of the past towards which we should turn our gaze. On the outside, the sunbathed lotuses in their alabastrine whiteness shines on the Temple’s sombre facade—a diamond cocooned in a gloomy, wooden shell. On the inside, poetry, education and intellectual sensibility have so far been treasured. But, for how long, Bui seems to implore, implicitly, thus examining the value of tradition over change. The only hope for the survival of past traditions is in the hands of Kien An (Nguyen Ngoc Hiep), the youngest of the lotus farmers, and the right candidate, the unravelling narrative tells us, to pass on the knowledge.

Take two: The Roundabout

After the initial sequence shot at the Temple, and for the whole duration of the film, Three Seasons’ montage cuts back and forth to the streets of Saigon. The viewer is continually jolted into the film’s other dimension, that of a city’s cacophony of sounds—where “old and new, capitalism and socialism, ancient and modern collide”. Tormented by cranes and new construction bulging like monsters everywhere, the city of Saigon weaves within itself its many tales. Yet, as this jostling city of corruption unravels before our eyes, we are presented with an alternative way, literally, a roundabout, where hope for the ‘nostalgic’ past will triumph. Hai (Dan Duong), a hardworking cyclo driver, whose street- life experiences allow him wisdom and kindness, inhabits the city’s most vital juncture: a colourful, heavily trafficked intersection that quickly becomes the film’s main feature. Literally a road junction where traffic is permitted to flow in one direction, the Roundabout in Three Seasons guides the passage of time as well, marking the lives of its many passers-by. On one side the Roundabout is flanked by a red wall emblazoned with ‘Coca-Cola’. Beneath the sign, Hai and his companion cyclo drivers rest, quenching their thirst not with the expensive drink advertised just behind them, but, conversely, with traditional pressed sugarcane concocted by the nearby stand also featured beneath the logo. This shot alone speaks to us on many levels. On the one hand, it speaks of the contrast between old and new, and the value of local, natural products against the seduction of imported goods; on the other, it signals, once again, Bui’s deliberate choice to partake in the vision of Vietnam as a disappearing paradise fuelled by America perception, rather than dismantling, in my opinion, “conventional ways in which Americans have seen Vietnam” as suggested by Michele Janette in her otherwise insightful reading of the film.

On the opposite side of the red wall there is Hager (Harvey Keitel), an ex-GI, who is overlooked by the cyclo drivers while he sits still, all day, on a camping chair, his back firmly set against his shabby hotel, his eyes focused on the restaurant where he last encountered his daughter’s Vietnamese mother. Hager’s steady presence at the Roundabout also functions as trait-d’union with Woody (Huu Duoc Nguyen), another main character. A young inhabitant of Saigon’s busy streets, Woody’s life epitomises a different urbandimension all together: that of the homeless, destitute child of the war, whose life is only worth occasional interactions with foreigners, buyers of his many trinkets. Bouncing our gaze from one to the other side of the Roundabout, we are exposed not only to the constant transition of people and goods, but also to the changes of daylight according to the people and their stories: sunny and bright over the red wall, where Hai’s modest life points to a brighter future, bleak and perplexing on Hager’s side, whose views on Vietnam are still stuck to the war, to shadowy and precarious on Woody’s occasional roaming of the site.

Take three: The Hotel

Towering over Saigon’s busy streets, the Hotel is a luxurious establishment, and, in Three Seasons, the indexical signifier of the ‘foreign’ and the ‘insidious’, the only space in the film whose threshold is traversed by most of the main characters. In fact, all excluding Kien An, whose virtuousness prevents her from entering the corrupted world, and Hai, who briefly inhabits the hotel to the end of redeeming Lan (Zoe Bui), the prostitute. Comfortably cushioned in air conditioning, the film all along is the sentiment that the Hotel is a place of transaction, a place where gain and loss chase each other in a continuum. Capitalism has its grip on it, its opulent décor makes no secret of that.

But there are many shades to Saigon’s urban life, as there are many hotels. There is in fact the hotel inhabited by Hager the “crazy guy”, as the film tells us, the former US Army officer, whose familiarity with Saigon makes him almost a local. His hotel, placed to counterbalance its foreign corollary, seems to belong to a different city: its unassuming exterior contrasts greatly with those of the grandness of the Hotel and so is its dark, damp interior juxtaposed to the Hotel’s brightly lit foyer. Notwithstanding its appearance of decay, Hager’s hotel comes across as secure and authentic. While prostitution happens in both localities, the luxurious and the rundown hotel, there are no pretentions in the latter. For instance, during Hager’s last dinner at the hotel, when he finally finds his daughter, we see the hotel guests and their accompanying girls carelessly exchanging food and intimacies. Such spontaneous behaviour seems to contrast with the code of conduct subscribed by the Hotel customers, where prostitution is portrayed as a sanitised act of transaction.

Inhabiting the spaces

Approaching the film from a spatial or ‘architectural’ perspective as proposed at the beginning of the paper— both in terms of analysing the spaces and how they function in the film, and in terms of mapping those very spaces within the filmic narrative—I have highlighted thus the extent to which Three Seasons employs manufactured or imagined locales. I have argued that the Temple, the Roundabout and the Hotel are the film’s real protagonists, corresponding to the notions of tradition, transition and transaction as charged referential indexicalities. However, there are other representative spaces in Three Seasons that should be equally explored in further research. For instance, the bar, artfully named Apocalypse Now, where Hagar and Woody have their only verbal exchange; the TV shop, whose premises Woody inhabits, if only temporarily; and the cinema, whose makeshift screen Woody traverses. There are also the restaurants: like the one where Hager has his last dinner in Saigon and meets his daughter for the first time. Lastly, and crucially, there is Lan’s private home, particularly her bedroom that should be viewed in parallel to the Hotel’s bedroom, both inhabited by Lan and Hai.

Through Bui’s performative use of these various locales as indexical cinematic spaces, the narrative of the film exposes the underlying, fundamental struggle with identity and cultural belonging the inhabitants of each specific locale are subjected to through their disjointed presence/absence. This staccato structure of the film is achieved not only by the film montage technique that works simultaneously on various chronological planes, but also by the characters’ peculiarity to each given space.

Their ethnographic specificity to each locale reflects, I would argue, Bui’s attempts to create an imagined or perceived space—a Vietnam he is estranged from and to which he is conforming. While the characters and their conduct seem, in fact, to be carved out of specific anthropological contexts—street life, prostitution, peasantry, military background and so on—in the film they also appear to be compelled into their roles and out of sync, so to speak, with their personae. While the actors play their roles, the roles themselves become an assumed, or clichéd ethnography of Vietnam that Bui would have adapted from mainstream American cinema. This spatial and cultural slippage between the actors and their personae has not so much to do with the acting per se, which is not within the scope of this paper, but in their atemporality in relation to their space and time. That is, the personae appear forcefully constructed to fit their identities, so to speak, within the performativity of the cinematic spaces and the narrative they unravel. This paradox describes a slippage that is partially due, this paper argues, to Tony Bui’s unfamiliarity with Vietnam despite being part of its diaspora, which had been overwhelmingly represented in the years following the end of the war by mainstream American film industry. On the other hand, the film does succeed partaking of both Vietnamese and American cinema by featuring established actors from the two countries, in this way, foregrounding a broader dialogue on the legacy of the war.

Produced in response to the mainstream film industry, how does Three Seasons intersect with its contemporary productions? In this short paper, I have done a formal and contextual analysis of the Three Seasons, examining the film’s attempts in counterbalancing Western appropriation of the war by giving an alternative voice and interpretation of the country’s past. I have argued that the film uses constructed cinematic spaces that possibly aggrandise the stereotype of Vietnam. This need for a clichéd, even if nostalgic, portrayal of the country is due to Bui and his diasporic audience’s attempts to reconcile their cross-cultural identity and remote familiarity to Vietnam—a land of great cultural transformation.

Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani graduated from the MA Asian Art Histories programme in 2011.

Three Seasons can be viewed here.