by Ramakrishnan Ramesh

Introduction

Artist residencies play an important role in facilitating meetings between diverse artists and collectives or art spaces, and generate new ways of thinking within the ecosystem that produce new ideas. Residencies mean different things to different people and are ever changing. Although the practice has been around for several years, each artist comes in with his or her own perceptions and expectations. Artist residencies are expected to ignite some change in the methods of working, challenge assumptions of time, space and process, and produce works or ideas that would not have happened otherwise. In this paper, I present some reflections from my own process of researching and creating. In any such encounter, several processes and negotiations occur, all of which have some value to both the space and the artist. Primary for me was the act of creating something, in this case photos and exhibition objects, within a defined time and space. Philosophically, I observed that the notion of a residency is not a fixed thing; it is an evolving thing, an open-ended process where art is meant to be created, presented and interpreted, and then the whole cycle repeats. Even as I write this, I can sense that I am having different thoughts about my own work and the processes that I followed, and these iterations are making me evolve as an artist and writer.

Background

After graduating with an MA in Asian Art Histories at LASALLE College of the Arts, I decided to develop my art and photography practice by taking up artist residencies. It is not all that common for graduates from art history programmes to undertake residencies, but I was keen since I had heard that many artists do their best work when away from their home base, in a different place and amongst other artists and people.

I came into the MA programme at LASALLE as a photographer and wannabe artist. I have been involved in the arts sector ever since my university days but my 30- year career was in business. I wanted to pursue my interest in photography at a different level, make it more than a hobby and get involved in the arts scene. However, the MA programme offered the flexibility to choose photography as an area of research, which I eventually did for my assignments and thesis. As a mature student, coming back to academia after three decades in corporate life, I was hungry for more intense experiences and ready for some experimentation and learning. My long-term objective is to contribute as an artist-researcher and do some teaching. As such, I felt that immersing myself in the art scene via artist residency programmes would benefit my learning, and give me direct experience with the contemporary art of the region.

I applied to several places for my residencies in Asia, including India and Japan. I found two that suited my needs and most importantly, the time and topic flexibility—one in Yogyakarta (also called Jogja) and another in Bangkok. In both these art spaces, I could do specific projects in photography and culture that blended well with their needs and scope.

Jogja: Ruang MES 56

My artist residency was at Ruang MES 56, a photography- based art collective run by photographers in Jogja, Indonesia. It was divided into two phases, each lasting roughly four weeks: Phase 1 from November to December 2018 and Phase 2 from January to February 2019. Ruang MES 56 is a non-profit institution established in 2002 by a group of artist-photographers. It mainly functions as a laboratory to spread photo-based art with a conceptual feel. The approach is exploratory and experimental with a nod to conceptual, historical and contextual work. Their mission is to delve into contemporary art discourse and visual culture in the Southeast Asian region through various programmes and activities such as residencies, presentations, discussions, exhibitions, and interdisciplinary art projects.

Ruang MES 56 is a very intense and creative hub with many things happening at the same time. It has a basic and primal feel about the space—just a few exhibition rooms, a small screening room and a rock-strewn foyer with a small open pantry (Fig. 1). The premises also house a music collective, a small eatery and shop that sells exhibition merchandise, T-shirts and beer. The visiting crowd is young and edgy, mostly students from local colleges. The space is what one would call ‘rough and ready’, and had its own unique atmosphere. The collective members even live on the premises and gave the place a lived-in feeling. Despite the lack of a formal structure, Ruang MES 56 attracts many artists from all over the world, and is considered a pit stop for many curators and collectors who pass through Jogja. Though informal and very open, they provide the core setup for mediators and integrators, bringing together international artists and incubating their ideas.

2019, Digital photograph

The name Ruang MES 56 comes from the old administrative term that denoted housing for government officials. It is located in the Mangkuyudan district with many galleries and other arts spaces nearby. Photographer, historian and curator Zhuang Wubin, in his publication, Photography in Southeast Asia, says that “this Yogyakarta-based collective is sometimes projected as [photography’s] sole exemplar. Blurring boundaries between art and life, the bohemian house not only serves as a working space, but is also where the artists live, sleep, socialise and party.”1 Over the years Ruang MES 56 has developed a strong sense of community and is seen as a helpful resource. Often, it is this spirit of gotong royong2 that is the prime aspect of the collective (Fig. 2).

2018-2019, Digital photograph

Jogja was the former capital of Java Island, a sultanate with a kraton and walled palace in the middle of the city. Jogja is considered the core of the art scene in Indonesia and Ruang MES 56 is a key part of this contemporary art scene, with several members taking their art to a regional and even international level. There is a special charm to Jogja, as it is the centre of Javanese culture, where old ways of life exist side-by-side with bustling modernity, says Tan Siuli, a curator at the Singapore Art Museum.3 Jogja is seen as a “happening” place with many openings, art shows and artist talks every weekend (Fig. 3). Many famous artists and photographers such as Heri Dono, Agus Suwage, FX Harsono and Eko Nugroho also come from this area or have studios in Jogja. During my brief stay, I was able to visit several of them, notably Heri Dono (who offered valuable suggestions for my Hidden Karma project) and also visited many other exhibition spaces. Jogja is also home to the seminal Cemeti – Institute for Art and Society and Sangkring Art Space which, among many other galleries, add to the vibrancy of the area.

My Reflections: Hidden Karma

Going into this residency, I was quite clear that I wanted to delve into some of the photography work I had done in the past at the Borobudur temple and revive it. As a photographer and co-creator, I had made photo books using images shot in Borobudur between 2009 and 2014. These photo books served as my starting point for going deeper into what I wanted to do in my residency. Additionally, I had access to the 160 photographs of the “hidden base” of Borobudur taken by Kassian Cephas4 from the KITLV, University of Leiden (Fig. 4). I was keen to re-present them in a contemporary venue and space, so as to add to the already growing interest and re-examine them in today’s context (Figs.5-7)

Figure 4 Photograph of Kassian Cephas (1845-1912), 19th century

Source: https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/imagecollection-kitlv

Right from the start, I realised that I was on my own and that there was no instruction or structure to the development of my project, specifically in the aspect of combining the historical photography of Borobudur and contemporary interpretation using my own photos. The members of Ruang MES 56 were delighted that I was working on something local but essentially left me alone after my initial presentation on the project. The first meeting I had with some of the founders of the MES 56 collective was so informal that it left me with a huge sensation of openness, that anything is possible, combined with some child-like excitement. I still recall what I had mumbled to Wowo, one of the senior directors of the Ruang MES 56 space: “I am just putting a few things in the pot, adding some spices and letting it cook. Let’s see what emerges.” He had no objections, and added that “cooking is good”.

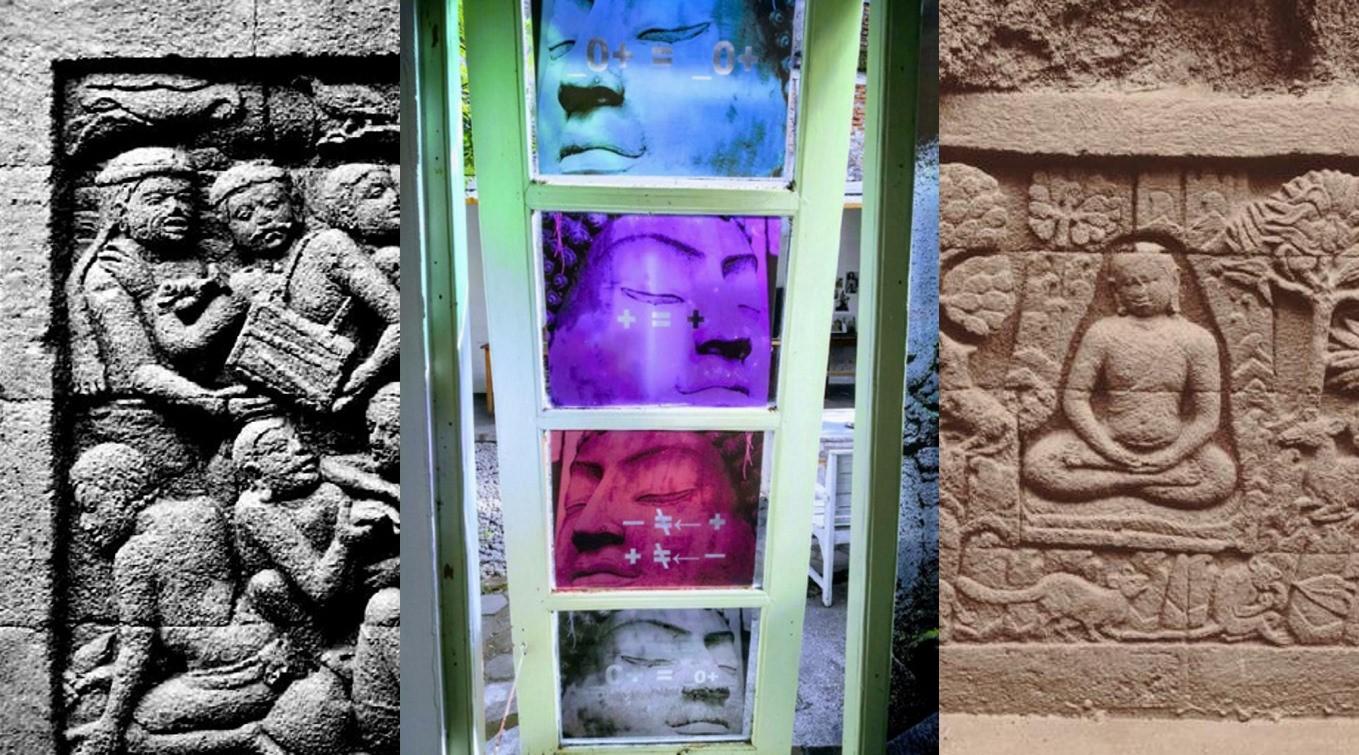

Figure 5 Kassian Cephas, 1845-1912

Life Activities, Relief panel from the “hidden base”, 1890-91, (digitally enhanced photo by author for this article)

Original Source: https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/search/kassian%20Cephas?type=edismax&cp=collection%3Akitlv_photos

Figure 6 Kassian Cephas, 1845-1912

4 Meditative Buddhas, Relief panel from the “hidden base”, 1890-91, (digitally enhanced by author for this article)

Source: https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/search/kassian%20Cephas?type=edismax&cp=collection%3Akitlv_photos

I am a photographer taking beginner steps as an artist and this was my first residency. Given all these, I decided I could work with a beginner’s mindset and explore different avenues. This turned out to be good as I got involved in a few projects that were beyond the scope of my work on Hidden Karma.5 In the first week of my research phase in late 2019, I made it a daily habit to visit several art spaces and galleries in the city, and began looking at contemporary art in a different way—a more open, free and unstructured way. I deliberately did not do anything about the project I was supposed to work on but instead allowed my mind to roam. My MA studies in LASALLE College had given me a good grounding on art history and critique but I still needed to learn more about curation and making art and photography to match site specific requirements.

The benefit of spending time outside of your home base is the chance to engage with other people, deal with unfamiliar spaces and see what everyone else is working on. This free exploration gave me several ideas and visiting other shows helped me to situate my presentation in a relevant context. Many of the shows and presentations I saw were large scale productions and well put-together. Seeing them helped me imagine my own work with reference to the space available in Ruang MES 56.

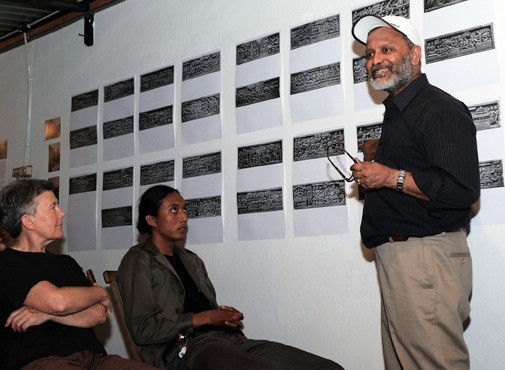

Development

At the end of Phase 1, I gave a talk about my research and the project’s scope. I put up 40 images of the “hidden base” (from the Kassian Cephas Archives, University of Leiden) on the wall in the foyer and invited people to comment on them (Fig. 8). Several local artists and friends of Ruang MES 56 were invited and many of them gave me their views. What surprised me was that many of them had not considered this rich set of panels and visuals as projects to work on even though they lie hidden so close to their backyards. These story-based relief panels are also referred to as the Karmavibhanga (the story of cause and effect in life, according to Buddhist philosophy) and remain buried under the Borobudur temple. Each of them is nearly 20 feet in length and they encircle the temple as its base foundation. They hold up the other levels of the temple and so the authorities in charge felt that it is better they remain buried, for structural reasons. Four of the 160 panels in the south east corner of the temple have been uncovered after the latest renovations and are now open for public viewing.

By analysing the content of these images and their links with Buddhist philosophy and texts, I wanted my project to shed light on these hidden treasures. During my research phase, I learned that the reasons that these images are hidden are not very clear and are often mixed up with ideas about bad karma and the sensitive and explicit nature of the images. There were also some controversies about the actual content of these relief panels, some deemed inappropriate or too sensitive or simply disagreeable, as well as the notion that it is not ‘safe’ to display or open them out.

Figure 10 Kassian Cephas, View of the “hidden base”, Borobudur Temple, taken at the time of digging and making photographs, Digital photograph,

Source: https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl

Kassian Cephas, the Sultanate’s official photographer in the 19th century, was entrusted with the task of documenting the panels before they were covered up with rock and stone. The process must have been laborious and quite a challenge but Cephas meticulously photographed each of these panels (Fig. 10). The originals are now in Holland with the University of Leiden archives.6 There is also a physical museum in the temple compound in Magelang in Borobudur that aims to show and tell the narrative of the Maha Karmavibhanga. My project was titled Hidden Karma: Reflections on the hidden base relief panel photographs. I was attempting to relook and review the Kassian Cephas images from several viewpoints and also to question the reasons for which these panels continue to be hidden.

There have been studies of these hidden panels but most of the knowledge is from an archaeological perspective. There are a few studies that also relate the text to the images and provide a link to some specific sutras. But there has not been an exploration of the images as a photographic process, nor a perspective on their content and, as far as I can tell, no one has directly questioned the reasons they are hidden. With this in mind, I wanted to locate my inquiry in the crosshairs of art history, Buddhist philosophical thought and photography. My aim was to engage with the artistic community and general viewers and begin a dialogue to relook at the images and see if they can in some way be opened up and displayed.

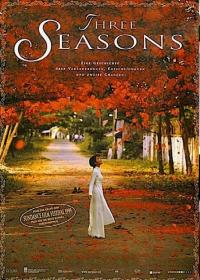

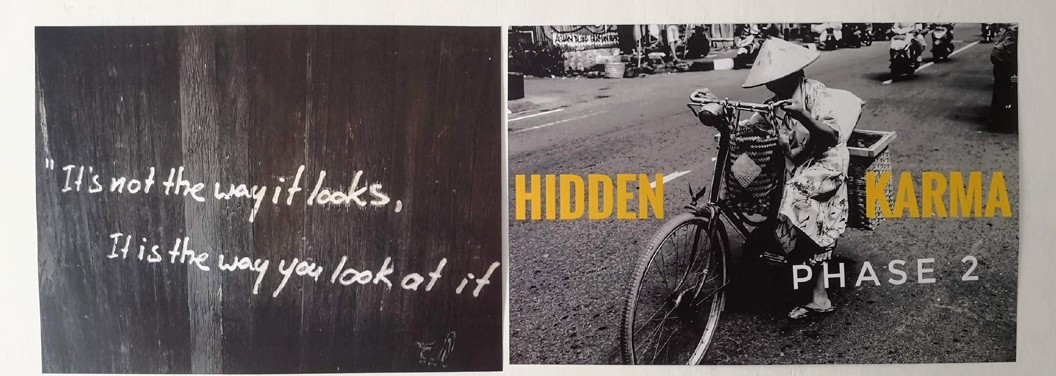

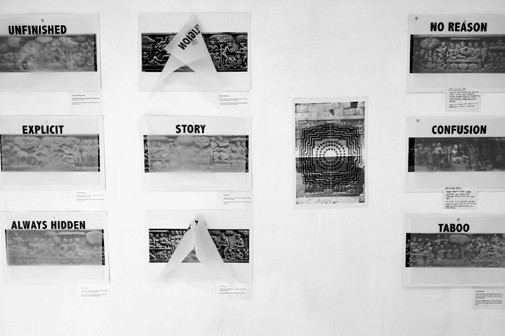

The Exhibition Mandala

All my research work from Phase 1, the exploration and study of the Kassian Cephas photographs, were printed in different formats. The curator and I jointly surveyed the available rooms in Ruang MES 56 and decided that we will exhibit several of these images befitting the project title: Hidden Karma. This exhibition, a final coming together of all the work, also served as a space to experiment with ways of creating and looking at images of the Karma Vibhanga relief panels. It was held in the Ruang MES 56 premises from 2 February 2019 to 19 February 2019. One of the photos displayed near the entrance clearly echoed the overall idea. “It is not the way it looks, it is the way you look at it” (Fig. 9). Some of the images are layered with the text from the Karma Vibhanga sutras to allow us to reflect on the ways photos and texts work together, while a few of the images are deliberately layered with penetrating filters and attempts to visualise the negative and positive nature of “emptiness”—a core teaching of Buddhism (Fig. 11). Our relationship with Buddhism (religion) and God is an ever-changing one which, at times, can become very transnational and commercial. Without being critical about Buddhist philosophy or the sutras, the photographs themselves are intended to work as visuals — to compare what we value and why. The exhibition then becomes a “mandala”, a world of images and messages that are interconnected and to be viewed as a whole and viewed as parts (Figs.12a and 12b).

The exhibition showed some of the Kassian Cephas images covered in translucent paper to suggest the hidden nature of their content. It also showed the key ideas that still hold us back from seeing the images for what they are. This method asks us to lift the veil, so to speak, to see the real truth and to deal with it. It is also meant to be an action (karma) that one has to do, to see the truth for oneself and not rely on myths and stories (Fig. 13).

The architecture of Borobudur itself was based on the mandala design. It is a physical structure showing the steps to reach Nirvana that simultaneously narrates the life of the Buddha and the Bodhisattvas. The Desire Realm or human world is at the base; as one goes up the temple, one moves up through the form worlds (Rupadhatu) and towards the formless (Arupadhatu) at the top. Likewise, if we compare the photographs in the exhibition to the panels, we can make the leap from the 9th century to today’s world, and vice versa. The exhibition takes the viewer on a journey, using contemporary images as stimuli. On one level, it asks us to question the world around us while, on another, to examine why we as people hide certain thoughts and ideas. The rest of the exhibition takes the concept of mandalas of expression and uses contemporary photographs to expound the narrative.

Other Encounters

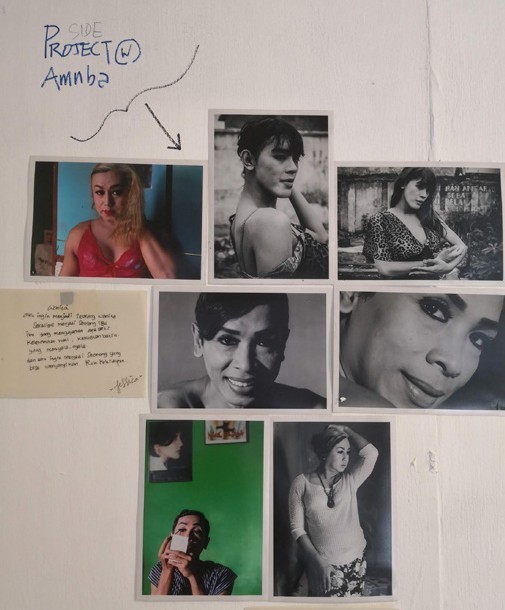

In Nov/Dec 2019, during Phase 1, Ruang MES 56 was supporting a group of new photographers from East Timor, coaching and guiding them in photography display and other ideas. I lent my camera equipment to one of the young artists from this group and worked with him in telling a story of a horse cart driver and his horse. Working with someone and sharing some techniques not only helped him but added value to my own artistic process. I was able to use some of the monochrome printing ideas from his work later in my project. I also had a chance to work on two other projects. In the first instance, I was invited to photograph a group of four transgender women who were living out of the city near the airport. I responded to this project immediately and with gusto as I had worked on the photography of transgender people for my MA thesis in 2018. To facilitate this process, Ruang MES 56 assigned me a student from the Art Institute in Jogja, Deni Fidinillah, to act as local translator and assistant. Deni was my go-between when I shot and interacted with the transgender women. I created a set of images, mainly atmospheric portraits of the transgender people in their homes and in and around Ruang MES 56. The photographs were presented in a cafe gallery alongside a performance focused on raising awareness about transgender issues. To give the photos a human touch, each of the individuals recorded their aspirations and dreams in a handwritten note in Bahasa Indonesia, which was then pinned to their image in the exhibition (Fig. 14).

In the second instance, I worked with Wimo Ambala Bayang, a senior member of Ruang MES 56. He had been working on landscape photographs taken near the river Progo that were used as part of the ‘say no’ to the construction of the New International Yogyakarta Airport project. For this project, Wimo and I travelled south to where the River Progo meets the sea, and photographed the changing lifestyle and landscapes of the area. We noticed huge changes in surrounding beachside villages where fisherfolks live. As a part of my exhibition, we were able to exhibit some photographs from the same location taken in the past, and compared them to what was happening in the present. I also used some found objects and wooden tree barks to suggest the transformation taking place in the area (Fig. 15).

Conclusion

In summary, after my Jogja Residency, I felt fulfilled. Firstly, I was happy that I had the chance to break up the project into two parts. I realised it was important for my artistic mind to shape up some ideas and also find the time and space to execute my vision. By having a break, I was able to let go of the project for a while and then to catch it again and bring it to fruition. I was also pleased that I had the opportunity to be involved in other projects. They helped me explore multiple ideas at the same time and also brought me the opportunity to work with others who helped me shape my photos to a specific narrative.

As for the specific nature of the projects that I undertook, I am particularly proud of the fact that I was able to respond to a request and produce exhibition-quality work in just a few days for the transgender project. I am also proud of the fact that the MA programme prepared me sufficiently to see things in their proper historical context. The MA programme thus gave me the confidence to talk about my work and my reasons for doing or creating things in the first place.

Moreover, viewing my own work from a distance and making choices on what goes up on the wall and why was very exciting even though I must admit that I did not always agree with what the curator had to say. I took some decisions on how the work should flow from one room to another and what it should look like in the end. Even though people walked about the galleries in a random way, putting a few works on the floor and making them read something towards the end gave some space for contemplation.

Finally, I developed some sense of the feelings and emotions that came up in the creating and thinking process of art, and how to work with them to meet a certain objective. On many occasions, I had to remind myself of my original objective: what am I creating? why did I decide to do this residency? The flow of work and ideas may not always have gone on as planned or expected but in the end, I produced work that I am proud of and made several friends along the way. There is a kind of alchemy in the process of working in a new place and with things away from one’s comfort zone. It was not comfortable at times, being with new people and working with strangers, but towards the end, the satisfaction one gets is well worth the deviations and the discomfort.

There is a basic trajectory to how these residencies work. It is a normal curve and it rises up over time—the trick is to keep it up there by creatively energising the project. In the end, it will come down, and the whole thing, when put together, feels different. Writing about the residency after nearly a year made me realise that the trajectory of Hidden Karma was the same. As the Buddha said, that is the nature of all things: they are born or created, they rise and grow over time, and in the end, they decline and eventually perish.

Ramakrishnan Ramesh graduated from the MA Asian Art Histories programme in 2018.