by Odile Calla-Simon

Contemporary art, by its own constant redefinition is an art of becoming, of happenings, occurrences and occasions.

Globalisation has affected the perceptions and presentations of contemporary art, exposing new grounds within the art world. If any characteristic of contemporary art directly entwines with the geopolitical transformations of the past three decades, it is the biennale phenomenon. Reflecting the politics of a global world in constant development, biennales have come to play an increasingly significant role in responding to the immediacy and flexibility of contemporary art’s development. As alternatives and more permeable terrains to the conservative “white cube” exhibition paradigm, biennales have proved to be critical platforms of inquiry, experimentation, innovation and risk-taking. They have arisen as an optimal ‘medium’ for curatorial strategies and discourses. Fostering a profusion of approaches, biennales are “sites of self-reflexive artistic practices, culturally inclusive discourses and critical articulations of difference”. Redefined and restructured, each edition of these exhibitions usually introduces radical changes and, as such, offers the potential to generate new frameworks and dialogues.

Within this context, since its launch in 2006, the Singapore Biennale has emerged as a key laboratory where exhibition strategies, methods and curatorial approaches could be tested, altered and re-invented. While the monolithic narratives of the first three Singapore Biennales successfully established Singapore’s own national and global position in relation to the arts of Southeast Asia, they were ultimately not able to achieve greater rootedness within the region. Both the 2013 and 2016 editions, in raising the critical need to approach contemporary art from the region away from the spectre of ‘global gaze’, highlighted the limits of any attempt to unify the region’s histories as a singular identity, given the multiple narratives in Southeast Asia. These previous editions have epitomised that at the core of a biennale is a need to cultivate edgier and riskier approaches to the point of accepting frustrations, if not failures, as a possible outcome. It is a biennale’s versatility and resilience which emphasises its full realisation.

Embracing the fact that one of the foremost opportunities of a biennale its constant potential to re-invent, the Singapore Biennale 2019, titled Every Step in the Right Direction undeniably initiated another curatorial turn under Patrick Flores’s artistic direction. Renouncing the classic schema of linear narrative for the original format of a “cross between a seminar and a festival, an archive and a workshop”, the collaborative curatorial team challenged audiences to take artistic journeys into current pressing circumstances and the changes they call for. Within this innovative curatorial strategy, Flores sought to trigger, “the ethical imperative for both artists and audiences to make choices and take the steps to think through what the world is facing right now and decide on how it can be different.” While ambitious, this broad reflection was intended to emphasise how art and artists, along with the engagement of audiences could contribute to the current realities and challenges of the world, becoming a catalyst for change. As an “experience” rather than a formal cultural affair, and based on the exchanges and interdisciplinarity stirred by the diversity of contemporary art in the region, the 2019 Singapore Biennale aimed to depict the social role and function of art in today’s societies.

The Biennale’s title draws from Filipina Salub Algabre’s statement about the failed peasant uprising she led against the mainstream nationalist movement, which was believed to be favouring landowners and not seeking genuine independence from the American colonialists: “No uprising fails. Each step is a step in the right direction.” As such, ‘Every Step in the Right Direction’ is an open invitation to go ahead. It articulates the necessary action of moving forward, the “right” direction only mattering within the context of the action one is willing to undertake. This idea of motion was reinforced by the curatorial choice to disperse the works across 11 sites in Singapore that, rather than just being a geographical spread of venues, compelled audiences to embark on a journey of multiple frameworks.

The Singapore Biennale 2019 established a moving trajectory with its non- thematic proposition/argument to reflect on and take action in a wide array of contemporary contexts. Whether through participatory and community- based projects or reflective, archival, discursive oriented works, artists and audiences alike were invited to explore a three-step process: (1) identifying and acknowledging the issues, (2) making decisions and initiating actions (3) enacting positive changes. If most of the artworks tackle contemporary themes that have arisen from globalisation, the three-part process created multiple dimensions, with participating artists covering perspectives such as individuals, communities, societies, contexts, boundaries, legacies and relationships in the past, present and future.

Step 1 – Identifying and acknowledging

Assessing the world’s current social, cultural, political states is an imperative element of the Biennale’s three-step process: without prior identification and acknowledgement, changes cannot occur. Flores and the Biennale’s curators prompt artists and viewers alike to recognise their place in the world and the reality of today’s critical circumstances. At a time when the region and the world face major crisis whether social (the rise of inequality, humanitarian and health emergencies), political (the rise of populism, nuclear proliferation and declines in freedom), or environmental (global warming, pollution and biodiversity loss), recognising and reflecting on them is imperative. Under the umbrella of the Biennale, artists become active correspondents who lay bare some of those crucial matters. Several exhibited works draw attention to the impact of climate change and the pressing need for action in favour of not only endangered species but entire complex ecosystems facing human interference. For instance, exploring the sounds of wildlife under threat, Zai Tang, in Escape Velocity III & IV, poetically captures the paradox between nature and the development of so-called wildlife eco-tourism destinations. Temsüyanger Longkumer’s series of terracotta sculptures, Parallel Communes, organically illustrates the flawed connection between nature and humanity. Others account for the evolution, or even more candidly the erosion, of nature, such as Ruangsak Anuwatwimon in his work Reincarnations (Hopea Sangal and Sindora Wallichii), and Zakaria Omar in Fossils of Shame: The Pillars. Likewise, Robert Zhao Renhui with his cabinet of curiosities, Queen’s Own Hill and its Environs, which featured more than 100 components including found objects, videos and photography, beckons viewers to engage closely with a historical narrative of the forest surrounding Gillman Barracks, including artist-led tours into this area.

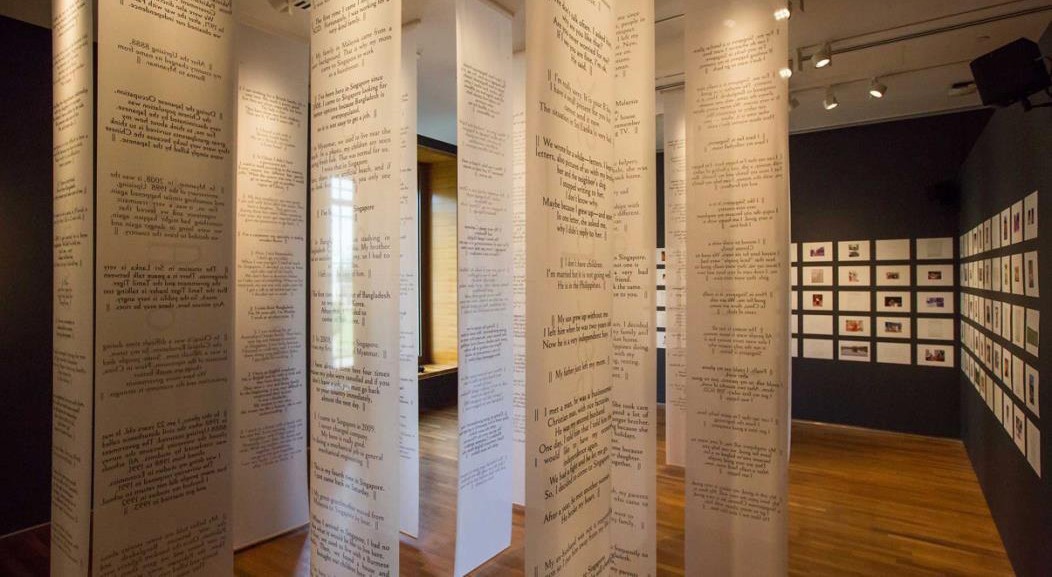

Societal issues are also substantially tackled in the exhibited works. Dennis Tan, with his work Many Waters to Cross, stresses the loss of tradition in the face of rapid globalisation, while Lim Sokchanlina highlights the marginalisation of a group of Khmer migrants in Shinjuku, Japan in his video installation Letters to the Sea. Going further, Verónica Troncoso, in Telling Stories from Outside and Inside, challenges visitors to stop, read and reflect on stereotyped communities often disregarded, with a powerful and confronting immersive installation of ceiling to floor scrolls on which narratives of migrant workers and local students she interviewed are documented. Walking through the scrolls and listening to related audio- recordings, viewers are defied to engage with the chronicles of migration and mobility across different generations in Singapore. The work visibly echoes both the feminist and post-colonial concept of ‘othering’ which critiques the treatment of some communities as “aliens” or inferiors. Most of these exhibited artworks emphasise societal issues that audiences could have easily overlooked if not directly confronted with them in context. As clarified by Flores, one reason why the process of acknowledgement is critical to the curatorial framework of the biennale is because “when one is able to understand what is happening in the work, one is also led to understanding what is happening in the world.”

Step 2 – Making decisions and initiating actions

Identification and recognition are, however, only one of the three segments of the journey that the curatorial team intended. If “change” is the outcome, then decisions must be crafted, and actions undertaken within the realms of the self and the community. As Mahatma Gandhi once said, “The future depends on what you do today.” While the choice of multiple venues for the Biennale already highlights this second phase, steps outlining what can be personally and collectively done are represented in the works of artists inviting audiences to participate and engage actively. Stepping into action is intrinsic to the work of Amanda Heng who, literally playing on the Biennale title, revisits her Let’s Walk series with Every Step Counts. Using a major element of her art practice, Heng invites the audience to reflect on the act of walking and its implications with regards to one’s body within rapidly evolving social and cultural environments. With An Obstacle in Every Direction, Nabilah Nordin playfully invites visitors to explore an obstacle course made from found objects, forming manifold possible paths and endings.

If one work truly epitomises the process of taking action, it is Sharon Chin’s In the Skin of a Tiger: Monument to What We Want (Tugu Kita). Prior to the opening of the Biennale, Sharon invited people to sew stitches on a series of banners made from recycled fabric cut out from discarded political flags that she collected after the 2018 historic Malaysian general election. This participatory performance project offers a clear invitation for people to contribute to the process of building their society as they aspire it to be.

If some of the numerous video installations do not seem to invite physical action, they unquestionably require the viewer to step back and reflect. Time and attention become of the essence in Marie Voignier’s Na China (1:10:00 mins), Okui Lala’s National Language Class: Our Language Proficiency (50:00 mins), or Vong Phaophanit and Claire Oboussier’s Never real historians, always near poets (41:51 mins). However, while some works engage audiences on clear

paths, others tend to convey highly intricate meanings for them to connect. Given the Biennale’s interest in research- based, archival and social practices (a rather substantial site of inquiry in contemporary art practice and theoretical discourse) the curatorial team invited artists elaborating on the function of the archive beyond a repository of documents, in order to develop contextual projects. As Flores explains, “context can be assessed through archival material. Artists today also engage in research; it is part of their practice and process. There is a shift from just using [art] as a form of expression, it goes beyond that now.” Thus, creatively using archives allows the artist to create work with the potential to deconstruct, build, reveal and connect differently with audiences. Such dense and complex works request greater engagement and action from audiences. Remaining unequivocal about the academic character of the Biennale, Flores intends the audience to go beyond just looking. Celine Condorelli’s complex Spatial Compositions 13, which spreads over three galleries at the National Gallery of Singapore, gathers the archives of five artists through an idiosyncratic personal perspective, with the act of curation becoming an artistic gesture.

The artist-curator incorporates beach-like lounge chairs inviting visitors to inhabit and occupy the space. These ‘support structures’ seem to either back the intricacy of the work and the mountains of information the viewer has to take in. Or, they might be seen as creating a more relaxed atmosphere and alleviating the complexity of the archives to render them more accessible. While the artist aspires for her work to create dialogues between viewers, the nexus and intellectual quality of the archives may still be too multifaceted for the audience to connect with and apprehend fully. Several other archival works request a deeper academic engagement from viewers. For instance, when the Biennale journey brought visitors to LASALLE College of the Arts where the works were, for the most part, complex to grasp. However, if archival installations such as Prapat Jiwarangsan’s Aesthetics 101 may be problematic for general audience to understand, the choice of the college as its site of display highlights the critical role of education in any process of change.

Step 3 – Process of change

The process of change is the Biennale’s significant last step towards what is collectively or individually decided upon as the right direction. If slightly elusive, this dimension is central to the three-step process envisioned by the curatorial team. For instance, once suspended, Sharon Chin’s monumental banners turn into a message of hope and start to symbolise an actual collective endeavour that may lead to constructive changes. If one person cannot change the world, each individual holds transformative potential.

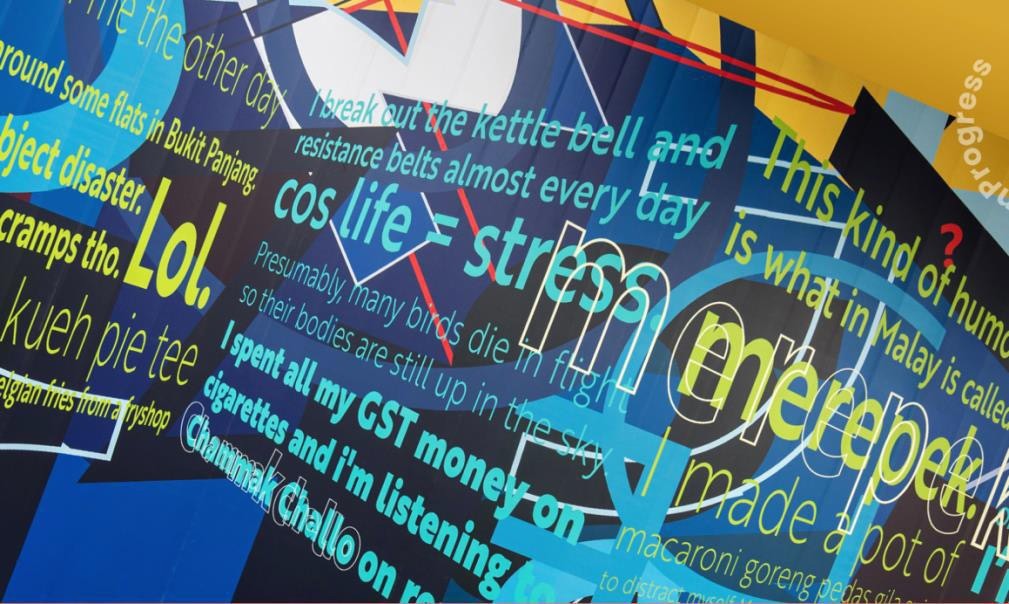

The aptitude that Pooja Nansi emphasises in Coping Mechanisms, reveals that positive changes can stem from everyday casual conversations and exchanges. As Flores states, he conceptualises, “change not only in terms of grand events like spectacular upheavals, but also in very personal, intimate, everyday endeavours. It doesn’t happen immediately. It takes time, patience and sustained commitment.” These are three factors that Min Thein Sung metaphorically symbolises with layers of particles settled on white canvases in his work, Time: Dust.

With its multiple narratives offering subtle but tangible changes, the 6th Singapore Biennale shows again that it is an essential cultural tool to build renewed perceptions of the environment, society, culture and politics, that is capable of responding to the phenomena of globalisation.

A dynamic platform that is transient and flexible in nature, there can be no denying that the Singapore Biennale’s ability to launch dialogues about enacting changes is already proving that “Every step is in the right direction.”

Odile Calla-Simon graduated from the MA Asian Art Histories programme in 2016.