Geraldine Lim, The Tunnel, 2019, MA Fine Arts graduation exhibition: Outside My Eye, 2019. Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, LASALLE College of the Arts.

by Kar-men Cheng, MA Fine Arts (2019)

In May this year, I visited my MAFA seniors’ graduation show Outside My Eye. It was their opening night and the atmosphere felt tense with promise. After all, this show is a culmination of one and a half years of research, positioning and repositioning. Camera flashes, backslapping and questions reverberated off the shiny grey floors of Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA)’s Gallery 1. The artists’ designated corners were enlivened with objects, environments, experiments, moments, and moods. Geraldine Lim tells me Outside My Eye was a random line taken from a children’s book. The cohort chose this title to emphasise experiences other than the visual as well as evoke the 'bodily aspect' of their practices. It was also important for the artists to acknowledge that their works were in some way shaped by the audiences that experience them.

I felt the need to find out more. The following interviews with the artists may convey some of the thoughts behind their practices.

Geraldine Lim

K: In your artist statement, you talk about exploring fantasy and the idealisation of the strange as a coping mechanism for confronting social anxiety. How did those feelings of anxiety inform the content of your fantasies and the aesthetic choices you make in the artwork?

Geraldine: Idealising the strange to me felt like a way to fight the thought of fear that is inherent in anxiety. The idea of the non-conforming is appealing to me as a form of revolt against normality and the general uncertainty of the under-represented. In that way, I think my work adopts a kind of 'monstrous' feminine language that deals with horror, that seems to come naturally from thinking about the idea of not belonging. I think a lot of it comes from thinking about the body system as a metaphor for my feelings towards people, when dealing with anxiety.

K: In that liminal space between your inner world of comfort and the external reality to which you feel disconnected, you have found a certain idea of 'strange'; for example, in The Tunnel, you have put the ‘strange’ in a physical form. Is it accurate to say that you develop your studio practice in tandem with your self-study?

Geraldine: Yes, my studio practice has increasingly became a way to process and confront my psychological issues and I think that in making The Tunnel, it seems like it has seamlessly fused together. After putting my thoughts into physicality, I felt like I was unloading the inside of my guts that have decayed, which I haven’t gotten rid of for a very long time.

K: You have also spoken about contributing to a narrative of psychological expulsion. How has this narrative evolved in the course of working on The Tunnel?

Geraldine: Before the execution of The Tunnel (the actual life-size tunnel that I can hide in), the psychological expulsion referred to the many 'creatures' that I made – metaphors for dispelling decayed and toxic matter in my body. The Tunnel was for me a way to hide from these organs that I had thrown away, but I realised they became a landscape from which I could not escape. I learned a lot over the semester as I was building this cave in my studio that I had to accept that they are never going away and that accepting them as my offspring is the only way to move forward...also, I can’t keep hiding from people. Maybe, ideally, I want both people and my creatures to cohabit less violently in my mind.

K: When making The Tunnel, how did you envision the viewer interacting with it?

Geraldine: In the beginning, till even today, I am ambivalent about anyone touching it. It feels strangely intimate for me to watch someone touch any of the creatures or interact with The Tunnel. Honestly, I just left my installation as it is because I didn’t think it was important to show whether I allowed touching or not. I think I just wanted to see if that strange feeling of intimacy goes away one day. I think that is the point for making this work—thinking about the audience, because I still have many uncertainties towards this idea of interaction.

K: Where is The Tunnel now?

Geraldine: I turned it into a blanket and kept it away, I don't have enough space at home (laughs).

ND Chow

K: I wanted to ask you something about your Instagram research into the idea of agency and exploitation. As you noted in your proposal, the current wave of feminism is about the woman’s right to be a sexual object if she chooses to be. In this way, an objectified subject reclaims her agency. At the same time, however, these images feed the larger visual discourse of sex in the media. How do you—as a man, and as a person who sometimes makes sensual images for work—think this reclaimed objectification affects the male gaze?

Chow: This is an interesting question. Philosophically speaking, having subjectivity of one’s own objectivity is an interesting problem. In my experiences as a professional photographer, as well as a student, managing subjectivity, objectification and gazes requires a balanced understanding of the intentions of the producers and audiences. In other words, the relationships between the formal aspects of an image and the likely perceptions of the relevant viewer. However, this agency comes with the responsibility of acknowledging the role of other forms of interpretation in the wider social context, which at times can have unintended consequences.

K: And could you speak about your relationship with your model—how did you come to become acquainted; were there any personal boundaries that the both of you intentionally set when you began the project?

Chow: I contacted my collaborator on Instagram via direct message. Within a week she replied. We corresponded through messages for a time, and then met in person to discuss our expectations and intentions. Following our conversations, we formulated a collaborative contract that outlined our working relationship. I have described how this collaborative exchange developed throughout the process in my thesis. I encourage interested readers to refer to this to see how our relationship unfolded and developed.

K: What surprised you about yourself during the course of this work? What were some of the challenges you faced as you set out to redefine the relationships you were so used to in your other photography work?

Chow: Primarily, what most surprised me about myself was how my perspective on the nature of photography - as a social medium for relationships and expression - changed and deepened across time and space. I came to see photographs, not as snapshots of frozen time, but as invitations to open-ended conversation and dialogue.

K: You mentioned that your subject kept a journal…I was wondering if you also made a mental or physical note of your own personal exploration of the relationships in photography?

Chow: Yes, I kept a journal throughout my studies. My thesis writing was an excellent platform for reflecting on and reorganising my thoughts. In this sense, my writing became an invaluable tool for artistic reflection. I also made a number of sketches, which I kept and continually referred to throughout the process.

K: I love how you had the nude model redo the photos with clothes on…would you say this novel experience invoked a different sort of vulnerability? How did it transform the work?

Chow: As our artistic relationship developed, we decided not to take nudes as a way to reimagine our work. It was interesting to have her put back on her own clothes. Unlike my experiences with staged fashion photography, having her wear her own clothes seemed to lend the images a new kind of honesty— almost like a new form of nude. Clothing is an important aspect of people’s identity and her wearing her clothes gave the images a sense of time and space in which comfortable clothes brought comfortable relationships, because this is how she presents herself outside the frame in daily life.

Chloe Po, In this labyrinth I dream of you, 2019, MA Fine Arts graduation exhibition: Outside My Eye, 2019, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, LASALLE College of the Arts.

Chloe Po, In this labyrinth I dream of you, 2019, MA Fine Arts graduation exhibition: Outside My Eye, 2019, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, LASALLE College of the Arts.

Chloe Po

K: There is a line in your proposal I found especially intriguing. You described your sculptures as exploring “a duality between a desire to dream of happiness while yearning for struggle.” Could you elaborate on the meaning of this line please?

Chloe: I believe there exists a duality in all things. Fantasy is something that possesses this same duality as it begins with a longing and endless search for happiness and ends with an inability to reach all that is initially dreamt or desired, resulting in a cycle of endless desires. I view this duality as a human yearning for struggle, a longing for the existence of fantasy and ability to fantasise.

K: In your sculptures, we see fragments of a house, and it’s tempting to see it as a setting for an autobiographical narrative…what kind of narrative would you wish the audience to take as they walk through your 'belongings'?

Chloe: I wish for the audience to construct their own narratives, so in a way, they are guided to form their own fantasies through their perceptions and experience of the sculptures.

K: Could you describe the process in creating these intricate sculptures? What kind of experiments led you to this final process?

Chloe: I discovered the material at a point in time when I was working with soap. I wanted a material that was more durable and yet similar to the texture and aesthetic that I was working with. In the process of constructing the material, time becomes a key focus and element as it involves a lot of patience and waiting. This became one of the key factors that I experimented with, the idea of craft and labour-intensive processes.

K: Your practice focuses heavily on the reverie which you defined in your proposal as 'fantasised time'. Could you speak a bit about what led to your interest in reveries? Does the reverie appear to you more as a 'what could have been' or a hopeful fantasy of possible futures?

Chloe: I am not a very happy person, and I think these disappointments drive the idea and need for fantasy or rather, reverie. I view reverie as an extension and refined quality of fantasised time. This essentially became my area of research. I investigated the reverie as a phenomenological experience, an encounter of a prolonged time within the mind. In that sense, reverie appears to me as a 'what could have been' taking on a rather melancholic expression.

K: Could you describe your personal study 'fragmentation of the self' and how you represented this concept in your work?

Chloe: I view the fragmentation of the self as a division and separation between the mind and body. The mind, through fantasising, transports the self and its existence into various self-constructed narratives. This is explored in my work through fragments of the house and elongated figures that are similar and yet differ from one another.

Shane Ng

K: Could you give some examples of the conditions and 'boundary conditions' that you are researching? What does this research process look like?

Shane: The conditions involved in my research are the elements of an environment—the colours, the structure as well as the assigned rules for the space. Boundary conditions are the borders of the conditions which if exceeded would cause a negative impact on the users of the space or space itself. An example of the condition and boundary conditions would be the library. In that environment the displays, colours and volume restrictions provide a suitable condition for reading; however, if the silence of the environment is not controlled, it may overwhelm and instead cause discomfort. My research process involves a series of mind maps which starts with the desirable elements of the space, branching out to the present conditions of the space and, according to the users or ideal projection, attempts to figure out their boundaries.

K: Does this testing of boundaries continue outside the greenware state?

Shane: It could. However the distortions of clay at bisque and glaze-fired state only ends up shattering to pieces so their outcome is more restricted. With these conditions in mind, and for the type of interactions that it would be subjected to, the material is more optimum in the greenware state than other fired states. One of the reasons why I worked largely with greenware clay is to test the conditions and boundary conditions of the space (exhibition space, and audiences included)—I can recycle the greenware and do more tests and save cost.

K: Could you describe the experimental structure that allowed you to balance intent and accident?

Shane: I used the triaxial axis to define the core of my experimentation followed by locating the secondary axis to see if the structure made 'sense'. The balance between intent and accident, in my opinion, is from giving both factors space to do what they do, be what they are, and be allowed to take their course.

K: What were some of the lessons (from other artists, readings, discussions, etc.) that helped you develop this experimental structure?

Shane: James Gibson’s Thoery of Affordances, Richard Sennet’s book The Craftsman, as well as my lecturer Lawrence Chin, helped me understand my experimented structures and what they can do.

K: How do you imagine furthering your practice now? Do you foresee continuing your current research themes in your work?

Shane: I see myself working on a series of fired ceramics with a different set of conditions from the ceramics that are commonly seen. I cannot say for certain how far this research would extend or whether it would stay in the realms of clay, but one thing that I am sure of is that I do not see an end to it yet.

JoJo

K: In your proposal, you said that your studio practice has spanned several art forms, as you 'transform text into other media by the concept of repetitions. Was it an organic process that took you from one medium to the next? How did you decide to use a particular medium?

JoJo: My studio practice starts with text then goes to other media. The reason I always start with text is because I believe language is the most powerful thing in the world - if you can control language you can control the world. That’s why I love language so much, that’s why I became a writer, hence even now as I focus on my art practice, I still go with text first. I use my text as some kind of guideline, to ensure my later practice does not go off the track. As for what is the medium after text, it really depends, depends on if the 'right texture' can fit the mood of my text, it’s a hard process, and hard to make a conclusion.

K: Your research into various philosophies of repetition has informed your own observations and practice with different types of repetitions. Is there something that unites all these experiences and iterations of repetitions for you?

JoJo: Yes there are many kinds of 'repetitions'. But I think what I’m going with mostly is the 'simple' repetition: repetition with the sameness, in order to view the results in the difference. What I believe is, the more simple the rule is, the more complex and beautiful results would come, in other words, repeat with the sameness is easy, but its consequences are varied and vast.

K: Which media translation presented you with surprising challenges? How did you overcome these challenges?

JoJo: I think the most challenging one is from text to video (not in the I’m bored video, but the ones from the first semester where I acted in my video). I didn’t develop these much, as it’s difficult to translate something already shown in text into a new image. I guess I still haven’t overcome the challenges. Maybe it’s because I know it’s not my strength, that I turned to sound/voice pieces. And in sound/voice pieces, the viewer can imagine their own image, but in video works you have to rely on the image I present to you.

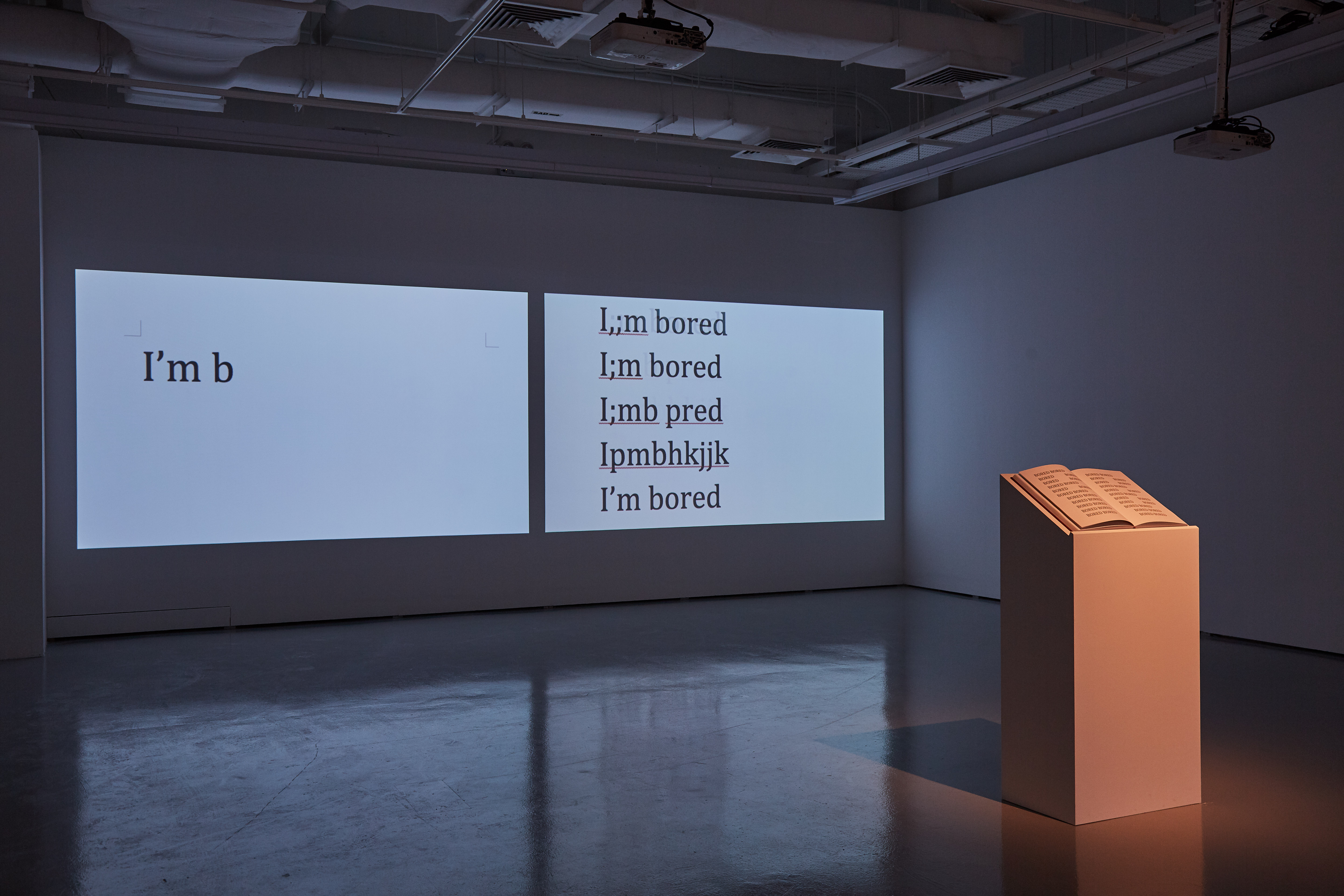

K: Your I’m bored video felt almost meditative to me. What was your experience as you were typing these sentences? What was going on in your head?

JoJo: I’m bored is a piece in which I kept on typing non-stop for 45 minutes in two separate pieces: one in fast speed and another in a slower speed. The experience of fast typing out 'I’m bored' resembles 'automatic writing'. I focused on typing 'I’m bored' for a little while, then I lost the attention or patience, and my mind started to wander off—my typing got messed up, and my mind kept wandering. Then my typing started to follow my mind, I typed what I was thinking. It was almost 'unconscious'. When I regained my 'consciousness', realising I was typing nonsense, I returned to typing 'I’m bored.' The experience of slow typing is more like an experience of experiencing time. The impact was a totally different feeling of 45 minutes.

Shen Xingzhou (JoJo), Diapsalmata, 2019; I’m bored, 2019, MA Fine Arts graduation exhibition: Outside My Eye, 2019, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, LASALLE College of the Arts.

K: How do the different parts of Diapsalmata IIIII—the manifesto, the book, the sound piece—inform each other? While working on each one, were you led onto new trains of thoughts towards the others?

JoJo: The book came first. To make a short conclusion I made the manifesto, then the video, and last was the sound piece. The relationship between the book and the video and the sound piece is similar to a triangle relation—linked to each other, impacting each other, together forming a whole. That’s the reason I set them up in the gallery in this way.

K: As you look back at your practice and how it developed in LASALLE, could you pinpoint one or two significant lessons, ideas or realisations that really impacted you?

JoJo: I think it can be the lesson that you should always be clear about what you want. Be clear about your idea. Clear enough to stay loyal to yourself.

Wen Qing

K: Did you take these photos with the intention of sharing them?

Wen Qing: Photos have primarily been a starting point for my works. At times these photos are taken consciously and at times as a record of things/ places that interest me when I go on walks or explore places that are new to me. When I took these photos, I had the intention of using them as inspiration but never thought that they would become the main subject-matter for my work.

K: What do you most want the audience to take away ie. a knowledge of what you went through on those dates, a feeling you had when you experienced the events, or some trait about yourself that can be gleaned from the images?

Wen Qing: I wanted my work to evoke feelings of memory and forgetting in the audience. The photos were meant to elicit feelings of nostalgia (from the viewer’s perspective), to get them to recall their own memories and experiences in places and non-places. My own experiences, while important to me since I had a personal attachment to them, were not what I wanted to leave the audience with. After all, an artwork is meant to be multi-faceted and open to multiple interpretations, depending on who’s viewing it and the context in which it is shown.

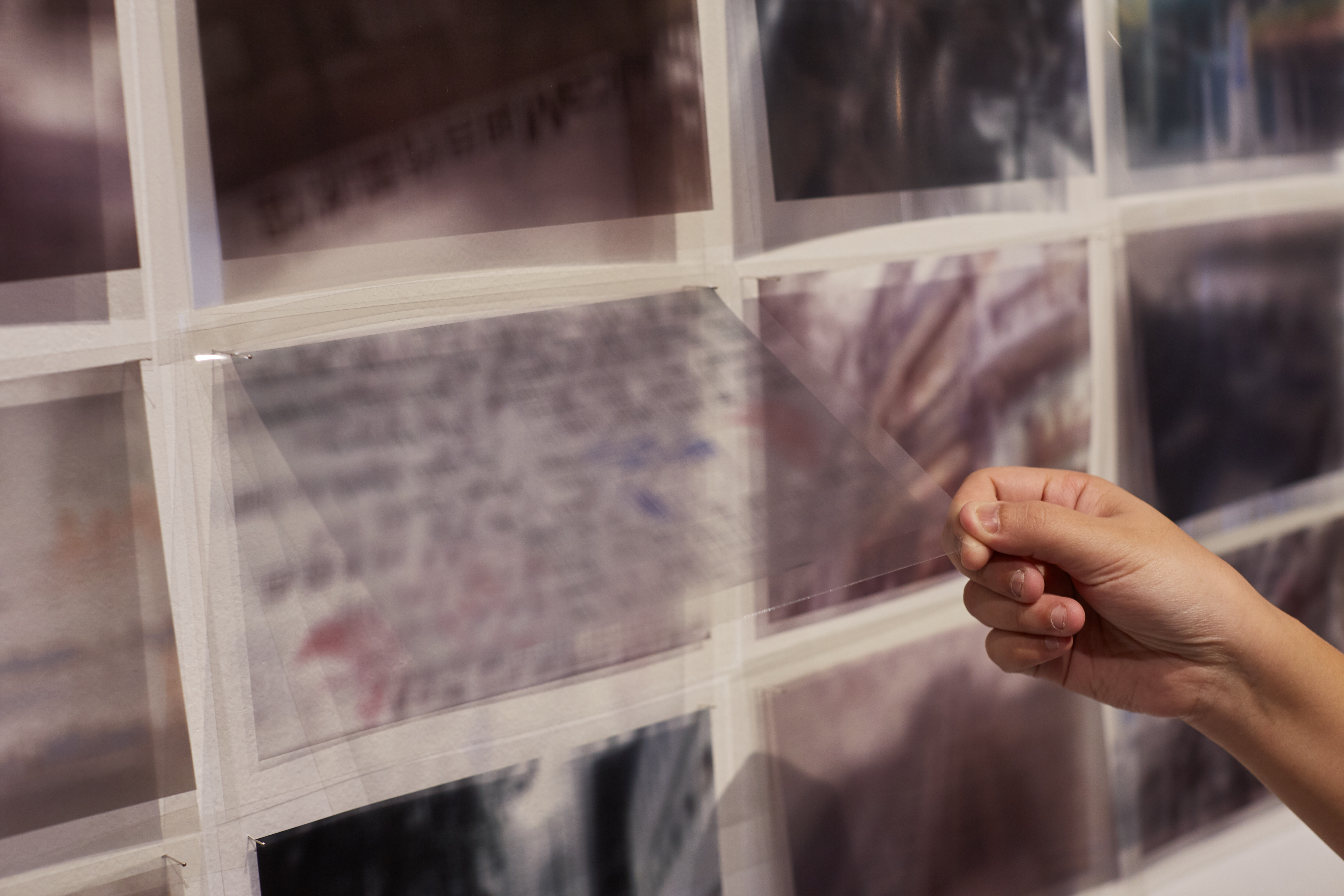

Kwek Wen Qing, Non-places: Reiseroute, 行程, Journey, 2019, MA Fine Arts graduation exhibition, Outside My Eye, 2019, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, LASALLE College of the Arts.

Kwek Wen Qing, Non-places: Reiseroute, 行程, Journey, 2019, MA Fine Arts graduation exhibition, Outside My Eye, 2019, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, LASALLE College of the Arts.

K: Could you talk a bit about the effects you had added into the photographs and the aesthetic you were going for?

Wen Qing: The highlights were a reference to the olden-day concept of hand-coloured photographs, where colours were painstakingly added onto the developed print. The colours were selected based on my memory of colours of these non-places rather than their actual colours.

K: Who is on the other end of these letter and postcard correspondences? What is the experience of sharing these personal stories with your audience?

Wen Qing: The photographs of postcards are photographs of actual correspondence with family and friends, sent while I was overseas on the Transcultural Collaboration programme. They contained the feelings I had at that particular point in time, expressed in written form, which complements the images taken. They are a written record of my emotions at that particular point in time.

K: What are some lessons or experiences from your time in LASALLE that informed the decisions that went into this work?

Wen Qing: This idea of transience gleaned from the trip helped to inform my work. My Transcultural Collaboration experience and what happened throughout that journey made me think intensely about what it means to journey through place to place, never residing in a particular place for long.

Liyana

K: The structure and materials used in Inhabiting the Banal, Imperfect and nothingness(B.I.N) reference those used in construction sites. Could you talk a bit about why you chose to focus on 'invisible labour' in the construction industry, and the research process that informed this work?

Liyana: I have been intrigued by the nature of imperfect things and the idea of the 'banal'—things that usually people don’t pay attention to. With this research, I study the nature of construction sites. I see the likeness of the 'invisible labour' akin to the invisible labour of the home—the endless hard work or labour that has been spent on a space. I would say it’s partly biographical as well. It’s like the constant invisible labour that I invest into any task given to me, growing up. There is always this need to share that in the works that I create. Consciously or subconsciously it’s there.

K: How has this project evolved over the course of this last year? Could you describe the initial inception of the idea, and the significant decisions you had to make that led to the final iteration?

Liyana: How it has evolved? I would say I gave myself a set of things that I knew I wanted in the work. It’s like a guideline that I will always fall on. For example, 'there should not be any colour.' Or 'no more than two materials at a time'. These sorts of guidelines in creating the work. You can even call it a 'checklist' so all other mock-ups or experimentation that does not fall in the checklist are put aside. However, I don’t dismiss them; I will eventually come back to them another day.

K: In your artist statement you mentioned how the work centres on 'the artist’s intervention between matter and form'—could you elaborate on this please?

Liyana: By the statement, 'the artist’s intervention between matter and form' I meant that the material that I use be allowed speak for itself to a certain extent before it begins to break or dry up. So I would place myself in that crucial moment where it is in its final stage of form.

K: How do you envision yourself further highlighting the overlooked and in-between processes in your practice?

Liyana: Looking at both the invisible labour from both the outside and the inside and merging them together. By incorporating ideas or objects found from these two areas. The construction sites of our surroundings will always be there but there are always new findings. Even if it is repeated, it’s never the same.

K: Is there anything else you’d like to address?

Liyana: In creating works there is always this channel or area that the artist has created for him/herself. For me this is a safe zone in which I can shut out everything from the outside world. It’s just me and the material/ process. It might sound weird but the minute I feel my back breaking and I begin to question the value of totally immersing myself in the particular process, I know I am creating the work right.

Johann Fauzi

(In the following interview with Johann Fauzi, some of the responses to my questions had been extracted from earlier recorded interviews provided by him, with his consent.)

K: You mentioned one of your central aims was to raise your audience’s awareness of the items’ provenance and the sociopolitical impact they had on the community which produced them. Did this happen? What were some of the questions or comments you received, or reactions you encountered from the viewers during the show?

Johann: There was a huge variety of opinion. Because I was showcasing works from my own art collection alongside my paintings, some felt as if I was merely showing off my own wealth. I didn’t know what to say to that, because that wasn’t my intention at all. I have been an art collector and artist for many years, so this showcase was an amalgamation of these different facets. Some viewers said that this installation allowed them access to a body of works they otherwise wouldn’t have been able to see.

I managed to have conversations with some audiences surrounding the decor and layout of the space as well. Some asked why the walls were painted red, and I pointed out that the colour red is commonly associated with ideas of bloodshed and anarchy. With colonialism, countries were plundered and lives were lost. I wanted the space to echo that history.

When I was preparing for the graduate showcase, some asked me to consider using the setting of local, Malay houses instead. Although that was a valid suggestion, I felt that using a local setting would not agree with viewers or bring out the subject matter in the same way. The discomfort that one feels from coming into such a rich and luxurious space creates, in turn, an acute awareness of the skewed and imbalanced power structures of the colonial era.

K: Could you describe the emotional experience of creating this collection?

Johann: I find the ecologies of things very interesting. With the furniture I incorporated into the space, I try to map out where all of the materials have come from. In Indonesia, for example, where the Dutch were in power for an extended period of time. In the graduate showcase, there were two ebony stools from my own art collection that I had included in the installation. These stools were originally made in Indonesia, and I had acquired them in Amsterdam. At the time these stools were made, ebony wood was an expensive and valuable product. One ebony stool would have been sold for the equivalent of two slaves. Humans were seen as yet another commodity; you could even trade them in for furniture.

When I do this sort of research, it breaks my heart. I enjoy making art, and these findings got me thinking about the human cost of the art I now create. Through these maps and objects, I wanted to open up these conversations around the ecologies of manufacture and consumption.

K: Your personal collection undoubtedly influences the art you make, and whoever purchases your art will bring forth the not-always-told narratives surrounding the provenance of these items. When these items are placed in another person’s sitting room, the frame changes and a new trajectory appears in their historical provenance. Is it important for you that all the routes leading to this new purchase is somehow apparent in the new context? How will you ensure the piece is considered with all the contexts surrounding its provenance?

Johann: I try to give viewers as much insight as possible into my thought process in putting an installation together. I have spoken to some viewers who have questioned my choice to depict Raffles as well. I wanted to critique the figure of Raffles against the backdrop of the Bicentennial. At the end of the day, everyone’s perspective on the matter is different and there is no single way of creating works in response to this period in time. I have had collectors purchase just one or two paintings out of a series of works, but I would love for a major institution to acquire the installation in its entirety. Of course it would be great if someone were to purchase the entire series. When you view these works together, they speak to each other and connections can be made between them. But it also comes down to the storage space one has, and what is practical.

K: How did LASALLE impact your studio practice?

Johann: It was quite difficult at first. I hadn’t read books for a long time. But the programme got me acquainted with research and writing again. My younger classmates have a very different way of thinking as well. They helped me see things from a very different perspective.

K: What are some of the questions that will guide your collecting/creating now?

Johann: I wanted to create awareness around the ecologies of capitalist consumerism. It is important to me that the objects I use in my installation reflect the exact time period I’m commenting on. For example, for the graduate showcase I invited a musician to perform in the space I had created. Instead of playing a repertoire that consisted of classical music, she played local Malay music. I wanted to intrigue viewers with that contrast, and I think it worked.

I created an incredibly lavish setting in which the paintings could be viewed, and this was important to me. Some viewers have commented on how inappropriate it feels, and how out of place some of them have felt amidst this luxury. I think it is important to visualise the sort of wealth that was accumulated by the colonial masters, as a result of their exploits in places such as Singapore, Java and India. Some might not have considered the extent of the colonial plunder before until they see it before them in such an overt way.

I’m working on an installation with a gallery at the moment, where I’ve been given free rein over four rooms. If a client wants to purchase a work, they’d have to purchase the entire wall. That will be interesting, and I’m looking forward to working on it.

Johann Fauzi, LASALLE Exhibition: MA Fine Arts graduation exhibition, Outside My Eye, 2019, in-situ installation view, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, LASALLE College of the Arts.