by Zulkhairi Zulkiflee, BA(Hons) Fine Arts Level 2 (2019)

Malais-a-trois (Mat) was a visual arts exhibition organised by Sobandwine (and Sikap) as a part of the former’s multi-artist, five short-termed shows named 2 3 3_j o o_c h i a t, aptly located at a rented 550 sq ft space in 233 Joo Chiat Road.

Malais-a-trois was conceived by myself, with the collaborative synergy of artists, Norah Lea and Farizi Noorfauzi. Here, the exhibition leveraged on Malayness as a loose point of departure.

The exhibition title plays with the term, Menage-a-trois, understood as “a domestic arrangement in which three people have romantic or sexual relations with each other, typically occupying the same household.” This was easily translated to a situation of three artists. Similarly, the title had a coincidental acronym of MAT, which is also a term mat, usually derogatory, describing a Malay male characterised as delinquent, unrefined and usually of lower education.

While mat may also be a neutral term reserved for Malay males in general, the term in the context of the exhibition seeks to serve as a self-deprecating and mostly, tongue-in- cheek reflection of the three artists.

The conversation below briefly captures the practices of Norah Lea, Farizi Noorfauzi and myself, which presents convenient affinities and nuanced differences.

Zulkhairi: Norah and Farizi, what are some personal impressions you have of Malais-a-trois?

Norah: I thought it was a fascinating introduction as to who we consider the mat to be! In society’s eyes we are all mats but then within this microcosm, we see the different layers, subtexts and identities! I find Zul’s use of repetition for his image intriguing in the sense that we search for something different within each photo, but actually it’s really just the same image. And I think that in itself could be a powerful move in response to the lack of representative images within the Malay community. At times maybe the act of representative images beyond the 4R and 5R print might even be taboo (family portraits aside) to the point of being accused of riak or arrogance just because it is not in line with the idea of merendah diri or humility.

Maybe, Malay people can afford to have a little less humility and start taking ownership of our own images.

Farizi’s work I think, is proof in the pudding of the next generation of visual artists. The idea is simple and powerful and it plays into the pun of kurung referring to baju kurung as well as to the meaning 'to restrict'. There is a tongue-in-cheek approach to Farizi’s works that I think is rather refreshing, especially in this current wave of artists tapping identity politics for their works. There are a lot of works based on trauma which are absolutely valid and I believe is the first step to healing, but to constantly be reminded of the pain can take a toll and maybe being to laugh at the pain once in a while will help us heal in ways we least expect.

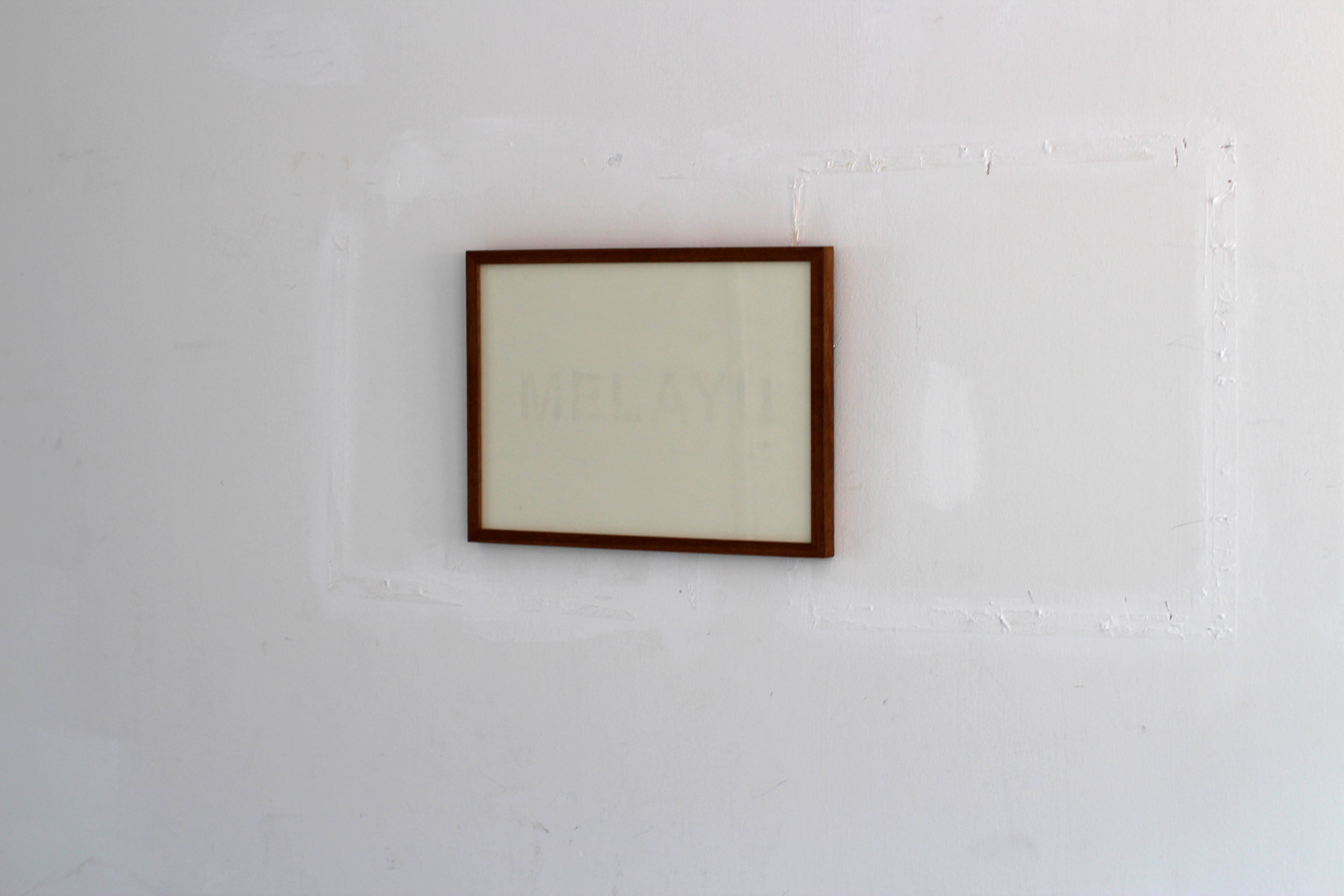

Zulkhairi: I was really thinking about the tension of visibility and invisibility, the latter being the work on the wall in which I had partially erased the word ‘Melayu’. Specifically, at that moment of time, I was interested in the idea of self-erasure (this extends beyond the making of the work) and how beyond one’s agency, it’s also a matter of choice of wanting to be seen (or not).

Farizi: I felt that Malais-a-trois was an intimate sharing of different ideas and meanings of what it’s like to be part of a minority community. I was most fond of how our works brought diverse interpretations to the forefront of the struggles in growing up as a Malay - Zul with the tension between visibility and invisibility; Norah with the politics of gender; and myself with questioning modern cultural relevancy.

Though I was at first sceptical of how the show would be received, within its short span of two days there were many interesting dialogues with people who came to see the show, all of which revealed to me that people do try to understand what we have to say about racial politics that is often too controversial for people to confront as a discourse. This was a pleasant surprise to me as the show was a revelation of the potential of more traction and visibility for the issues we were dealing with, such as the different ‘minority experiences’. I also feel that the heterogenity that comes with the diversity in issues each of us dealt with in our works fights against the general stereotype that ‘most Malay artists just deal with what it means to be Malay’ and in some sense the show allowed us to delve into a deeper discussion of the topic for which I am glad because the Malay culture has become easy to homogenous, generalise and stereotype.

Zulkhairi: Norah, with the work you showed, I feel you were also trying to reveal something not often spoken about, due to it being taboo. What was some impetus in making the work?

Norah: I’m really intrigued and I think more than anything, charmed by ethnographic portraits in the early history of photography. Despite most of these images being used for scientific documents, you really cannot take away the bias of colonial photographers behind the lens of the camera. Subjects in ethnographic portraits are more or less portrayed in a very exoticised manner.

That being said, I am aware of Kassian Cephas’ body of work and I absolutely adore his work. He is Java’s first photographer and that’s really powerful!

Similarly with Ethnographic Portrait of a Bugis Calabai, I wanted to imagine myself being a person like Cephas who in his time assert myself and my own existence within the history of the region. My grandfather is of Bugis ancestry but he is very much Malay-nised. All I know of Bugis people is from my Javanese grandmother’s tales of how they were fierce lanun people, or pirates. Nobody told me that the Bugis people accepted up to five gender variations and that despite colonisation and Islamisation of the region, this tradition persists till today.

Bugis history is very much part of Singapore’s history having a place called Bugis Street itself, once notorious for gay sailors and trans sex workers. It goes to show that queerness is inherent in the fabric of our society and it is not a coincidence that the people the street is named after had a more inclusive understanding of gender(s).

I would say that the portrait in itself is an exercise of resistance, that you cannot silence something that has always been there. What you try to hide in the dark will come to light, one way or another.

Zulkhairi: Farizi, is humour an important aspect in your work?

Farizi: In my works, humour is definitely a real approach but has never been super intentional. I try to approach my works in both absurd yet subtle/neutral ways, so it encourages a sense of irony and humour in the audiences interpretation, which to me has become quite significant. Dealing with the matrix of identity and in ideas like whether culture is important is a touchy subject and I’ve always been afraid to confront it directly, so humour is an indirect confrontation with the issues I deal with, and is valuable as it encourages viewers to engage with (the issues in) my works.

Zulkhairi: With the dialogues you mentioned Farizi, do both of you feel that with difference, a sense of engagement with a wider audience can be limited sometimes? What are some of your strategies in ensuring there are enough entry points for people of other worldviews and lived experiences?

Norah: I think I’m not interested in acceptance or understanding of a 'wider' view, what I’m interested is making content/ conversation that is accessible to my primary audience (mainly marginalised folks i.e queer/brown/Malay/queer and brown/ queer and Malay) and empowering ourselves with images that they can feel like “Hey I can be that! I can do that!” I say accessibility because not everyone from the intersections of communities that I address are on the same page, are well acquainted with ideas that I consider myself to be privileged enough to have access to because of academia.

Sometimes we tend to make art with a lot of theories rooted in academic thought, but we forget who it is for. It is important for me especially, because I’m riding on the wave of identity politics to empower myself and to see more of myself, but if people who look like me or live lives like me can’t relate, then I guess my work is more or less indulgent and I would even dare say narcissistic.

Zulkhairi: Farizi, do you feel the same? Are you concerned with having a wider audience?

Farizi: I feel the same as Norah on this, because my interest is in making the conversation accessible; but because my works deal with the idea of being people and communal and overcoming polarising ideas such as culture and race, I feel like I want to make my works accessible to as many people as possible. In that regard I’m not interested in a wider audience, but I am primarily interested in making my works as accessible as possible, such that an audience becomes secondary. Hence when I am making my works I am not so concerned about having a larger audience, but more about how do I make sure that every person who views my works leave questioning the same things I question in my works.

Norah: Would you almost say that there is an element of universality with regards to the subjects you work on?

Farizi: I do acknowledge that when dealing with identity politics it can be very foreign and strange for a viewer because they engage in issues they don’t usually concern themselves with. I wouldn’t say for sure but I try to universalise the subjects I work on without straying too far from the issue, because while I work on issues that deal with the Malay identity, my body of work in general engages with the idea of cultural relevance, so while some of my works can be ‘Malay-centric’, I am still questioning the relevance of culture but only by using the malay culture as a point of departure.

Norah: Yes! I thought that the idea of 'performing' a cultural identity would resonate, even with people of different cultural identities, especially for people of our time.

Zulkhairi: I think I would like to comment on the idea of universality as put forth by Norah. Even though our pursuits often involve issues of identity/ ethnicity, no matter how intersectional this may be, we also adopt visual codes and signifiers that are identifiable from a visual language point of view. Thus to some extent, even though I may speak of a unique experience, I leverage on art historical references as a form of ‘levelling field’ especially to those who are not privy to my full experience.

If I may, echoing Farizi’s interest in questioning the relevance of culture and I suppose, the Malay identity, we often hear people question the relevance of identity in a postmodern sense. What are your opinions on this? Is there a need to talk about identity at all, or at least in the context of Singapore?

Farizi: I think the need for an identity is important in the sociocultural matrix of Singapore, which ironically has a lack of a national identity even within its diasporic intersections. But as such the Singaporean identity is a kind of transformative space that embraces the development of different individual identities. The keyword here is individuality – we see the liberalisation of selves within the general younger generations, but not enough people exploit the potential of individualism in this country. Hence while our sense of identity started with the idea of ‘CMIO’, it is always important to question where we came from, i.e. our cultural traditions, instead of blindly accepting them as our sense of identity (we are people, not sheep). We realise that Singapore is more progressive and more liberal, and hence our tropes of self understanding should progress from multi-culturalism to multi-individualism.

Norah: I think my sentiments more or less echo what Farizi feels! To summarise, I feel that there is room for multiple narratives instead of one-faceted identities.

Zulkhairi: Farizi, it’s interesting how you see a transformative quality with identity and how this similarly possesses a potentiality for a more complex sense of individualism. If I may, you mentioned tropes and how this have obviously limited one’s self-understanding (and the need to expand it), yet I do wonder how one constructs a liberal sense of individualism?

In this exhibition for instance, the idea of ‘mat’ is put forth in a self-deprecating manner. While a general understanding of what ‘mat’ means may have already been established, it has become a knee jerk reaction to prove one is otherwise due to its associations with certain attributes. Thus, it’s quite natural to discount such aspects in the process of one’s individuation. But with such things that we choose to stay away from, can we extrapolate the transformative potential you alluded to as a way to reclaim a form of mat-ness?

Norah: Zul, do you think it’s possible to 'appropriate' mat culture?’

Zulkhairi: I think there may be various understanding of what a mat is but naturally, it’s a layman term that denotes quite a hypermasculine delinquent (or at least, mischievous) who is working-class in nature. Yet, while this may seem quite simple, I think even the mat often breaks away from traditional codes of masculinity, for instance, being expressive (i. e. emotion) through music and singing, or even adopting certain beauty regimes like eyebrow trimming.

What I really mean to say is, even something seemingly ‘simple’ like the ‘mat’ possesses multiple dimensions. And if we add a subcultural layer to this, it really depends whether we are interpreting the mat based a a semiotic lens (how the group looks like collectively), the group’s argot (the way they speak) or even demeanour (the way they behave). It’s basically in the mode of becoming so to speak! And with technology mediating their (or rather, our) visibility, we are seeing a synthesis of identity signifiers that can be seen as intercultural! So to answer you Norah, perhaps, we are already appropriating such a ‘culture’ (whatever this entails!). Based on the three categories outlined above, I think it’s just a matter of performance, transformation and perhaps, even queering.

Norah: I really like the idea of synthesis of identity signifiers! I mean, the Malay identity in itself is a synthesis of so many influences constantly packaged and repackaged. I guess to wrap things up Zul, how would you package and repackage future renditions of Malais-a-trois (if you do intend to do future renditions someday!)? Or rather, what are other things you would hope to explore and expand on should there be a future rendition of Malais-a-trois?

Zulkhairi: I think that’s a great question! Firstly of course, I hope the second iteration could last more than two days! Also, I would really like to consider for a more formal venue just so the works can be properly contextualised with in-depth analysis made. I think it will be interesting to retain some of the original works with additions of new developments. Essentially, I hope the show was able to act as an extension to all our practices where respective works were able to value add and contribute certain complexities beyond an individuated reading. And finally, thank you both for being part of the show!

Also, thank you Sobandwine (https://www.sobandwine.com) for the generosity in hosting us!

Malais-a-trois (Mat) was recently developed as MAT for the Curator Open Call as initiated by Objectifs, Centre for Photography & Film. The exhibition ran from 2 August to 15 September 2019.

NORAH LEA (b. 1993, Singapore)

An artist whose works investigate the performative aspects of our identities. Her work is rooted in self-portraiture, exploring themes such as gender, sexuality and ethnicity through photography, film and performance. She is currently in her final year of studies in Photography and Digital Imaging and will be graduating from a Bachelor of Fine Arts in the NTU’s School of Art, Design and Media by 2019.

http://www.norahlea.com

FARIZI NOORFAUZI (b. 1998, Singapore)

A multi-disciplinary artist in Singapore who works predominantly with media and performance art. He is interested in investigating the relevance of culture, specifically within the unique socio-cultural context of Singapore as an intersection of diasporic cultures.

http://www.cargocollective.com/farizi

ZULKHAIRI ZULKIFLEE (b. 1991, Singapore)

A visual artist and exhibition-maker based in Singapore. His practice explores the notion of

Malayness in relation to knowledge production, the social agency and distinction/ taste.

http://www.cargocollective.com/zulkhairizulkiflee

https://www.facebook.com/sikapgroup