Design thinking has become a trendy buzzword even beyond the design sector. Be it in the realms of public policy, tech or finance, the ability to think like a designer is increasingly prized as a means to solve problems in a creative and innovative way.

However, design is not merely a paper exercise in generating solutions. Instead, it calls on designers to be self-reflexive about their process, consider the implication of their design action, as well as view design through transdisciplinary perspectives in order to better understand the complexities of problems. The journey is just as important, if not moreso, than the destination.

At LASALLE College of the Arts’ MA Design programme, the residency programme – which students undertake between the first and second semester – is integral to this journey. “This off-site learning experience provides students with real-life scenarios to further test and develop initial ideas with research centres, design incubators, creative agencies and organisations,” says Lecturer-in-Charge Dr Harah Chon. “As design is a discipline of shifting knowing into doing, the residency allows students to explore theoretical perspectives through practical applications.”

For current MA Design students Ramya Chandran (right) and Jayal Shroff (left), being able to synthesise conceptual learning with practical application was central to why they chose to study at LASALLE. Jayal, a veteran designer with two decades of experience, had visited previous MA Design graduation showcases and was inspired by the programme’s emphasis on the use of design to solve social problems. “My motivation for joining the programme was mainly to augment my competency in social impact projects,” she explains, having pivoted midway in her career from corporate clients to social projects related to safety, health and finance.

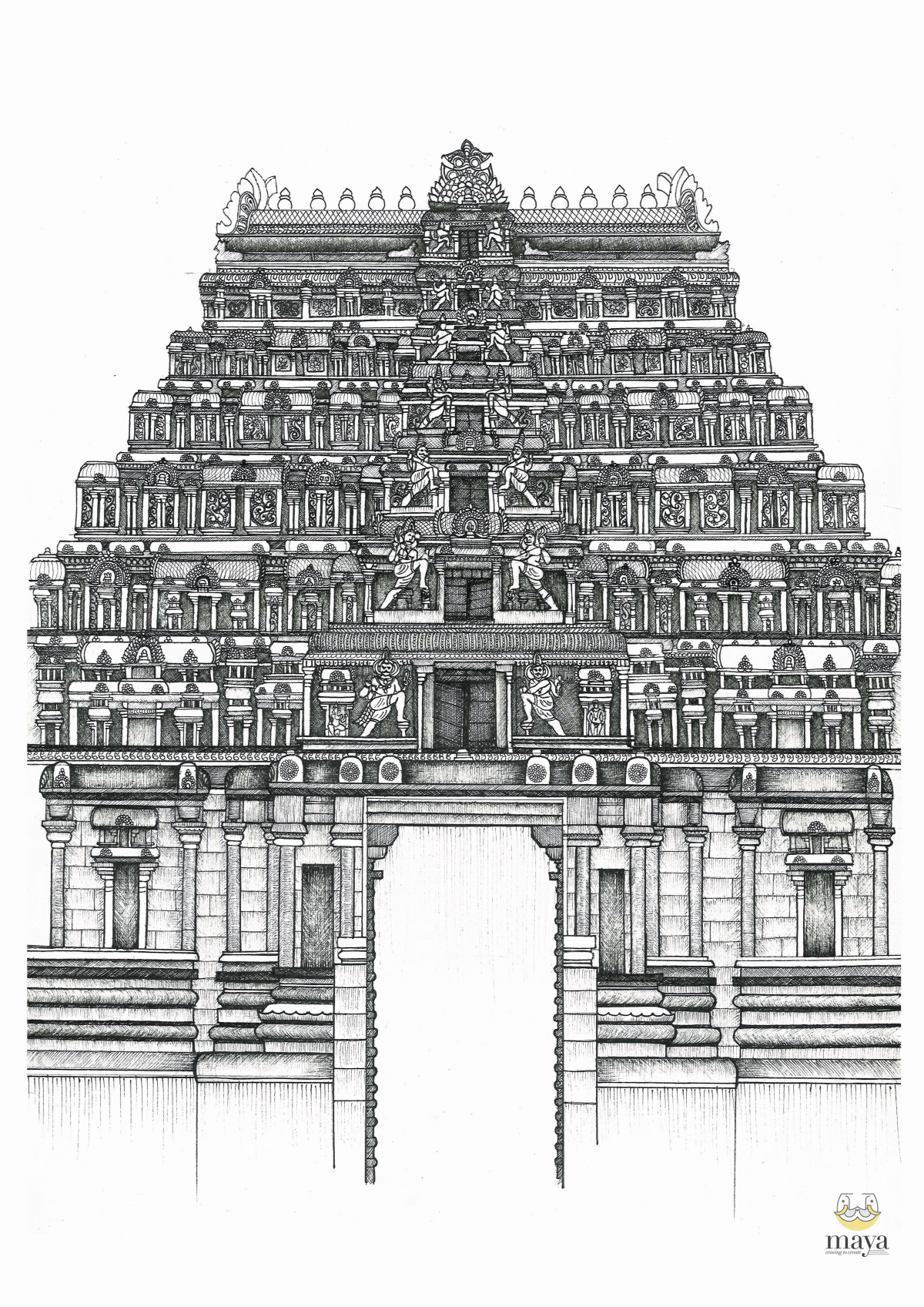

A temple sketch by Ramya

Ramya also enrolled in the programme with an intention to tackle a cultural and social problem. A graphic designer and illustrator, she had begun to branch out into architectural sketches, taking commissions via an Instagram page she runs with her sister. As clients increasingly commissioned her to illustrate temples and heritage homes in India, Ramya noticed the lack of awareness of India’s own temple heritage amongst the younger generation. She decided to apply to the MA Design programme to see how design could help to change mindsets and perspectives about heritage.

Creating little shifts in behaviour that go a long way for sustainability

When Jayal reflected on her childhood in Mumbai in the 1980s, she realised that there was a mindfulness around buying, preserving and discarding things. Her family would gather old clothes, newspapers and broken furniture to scrap and rarely generated more waste than what could be contained in a single dustbin in her family home. Coupled with her research that revealed that social innovations in sustainability are typically initiated by the citizenry instead of governments, Jayal is concerned with how we can revive the same mindfulness in everyday behaviours and habits that used to be present 20 to 30 years ago.

During her residency at the Lien Centre for Social Innovation, Jayal worked with mentors Tania Nagpaul and Eunice Low who helped her to distill her research, reflections and recommendations for the centre’s flagship content platform Social Space. Her first article explores how individuals could incorporate thrifty habits from the past that would lead to systemic change. Jayal also worked on an explainer article that delves into the core philosophies of innovations such as the circular economy, voluntary simplicity, the sharing economy and the slow movement. It surfaces the commonalities that help to change mindsets and behaviours, thus lead to lasting change in sustainability.

“While little shifts in habits and behaviours can go a long way towards helping or harming the planet. Convenience, ease and economy broadly impact whether these new behaviours and habits take root,” Jayal notes. “As a designer, my role is to create something that would easily fit into people's daily routines and more importantly, be seen as emotionally desirable.”

Jayal’s interest in influencing behaviour was complemented by another residency she undertook with FinalMile, a company which researches the heuristics, biases and emotions behind people’s decisions and behaviours. Jayal designed a game called Metrologic which called on players to choose from three conundrum-evoking choices in response to a scenario. Through the process of game design, interviews, focus groups, data analysis and creation of frameworks to help understand the data, Jayal was able to better understand the beliefs, attitudes, perceptions and lifestyles of Singaporeans, which will inform her work as she moves towards her thesis project.

“Constraints lead to creative thinking”

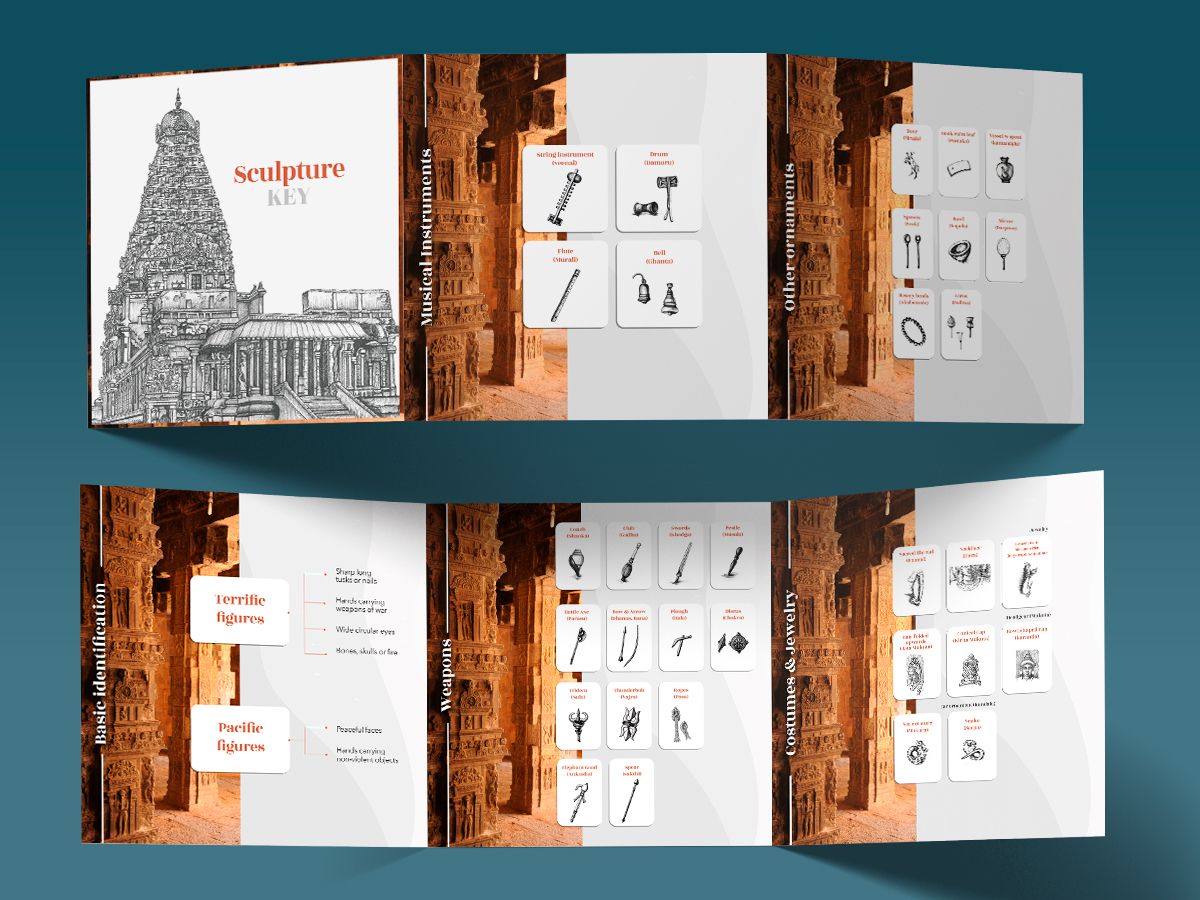

Ramya’s passion for reviving interest in heritage Indian temples led to a residency with the Tamil Heritage Trust, a non-profit organisation run by a group of heritage enthusiasts in Chennai. She was mentored by Tamil Heritage Trust co-founder Prof S. Swaminathan, and tapped on his extensive knowledge about temple iconography and architecture.

However, with the strict travel restrictions brought upon by the COVID-19 pandemic, Ramya was unable to return to India. Forced to work remotely, she had to creatively recalibrate her residency to facilitate remote data collection. Instead of collecting data in person at temples, she switched gears to gather participant observation data through an online activity kit that would be used during virtual tours of the two temples.

Moving online brought about unexpected benefits to Ramya’s research – suddenly she was able to reach out to people all over the world, not just in Tamil Nadu. Furthermore, as many participants were unable to travel back to their hometowns for their planned holidays, the exercise provided participants with an avenue to relive a temple experience. This emotional undercurrent greatly added to Ramya’s research insights about the connections between people and architecture.

The residency also had the added effect of reinvigorating Ramya’s love of design. “The thought of quantitative research and data collection has always made the idea of research feel very laborious to me! But design opens up these avenues of using one's creativity to develop interesting ways of interacting with the public, getting them to unconsciously put their guard down and using triggers to entice and interpret information.”

For both Ramya and Jayal, their residencies enabled them to gain new clarity about their research projects. “At the end of the first semester, I had explored all of these separate elements of heritage management, Indian temple architecture and iconography, and human-centric problem solving approaches. The residency greatly helped to consolidate these elements in preparation for the practice element or the ‘making’,” says Ramya.

Jayal concurs. “My project has sharpened in focus, and my improved knowledge about the issue and context has given me the confidence to now think about more innovative approaches and solutions.”

As they enter their second semester, Jayal and Ramya are ready to tackle their research projects with a newfound confidence. “Like many creatives, I wanted to use my skills to solve real world problems but felt like my creativity would not be enough to take up such a huge responsibility. The MA Design programme gives you that gateway – it teaches you how to use interdisciplinary approaches and tackle an issue in a way that is fruitful, while gradually expanding your scope of knowledge,” said Ramya.

“Even for professionals with experience, there is a lot to learn as well as unlearn,” adds Jayal. “The programme forces you to relook a given problem through a variety of lenses. While lecturers help to broaden perspectives, the student is allowed to customise their own approach to the project and make it their own.”

Apply now for our postgraduate programmes.