Patrick Flores, the artistic director for Singapore Biennale 2019, insists that this year’s biennale doesn’t have a theme. The title “Every Step in the Right Direction” is an invitation, an inspiration, he says; not a theme.

“I believe in certain anxieties and they don't have to become themes. Themes tend to capture, instead of release,” he explains.

Flores, along with six other curators, formed the biennale mainly in terms of geography, wanting to focus on Southeast Asia and at the same time extending beyond Southeast Asia, through the rest of the world’s interaction with the region. “I was interested in the Pacific, that's why I got artists from the States, [such as] Carlos Villa, Miljohn Ruperto, and Alfonso Ossorio,” he says. “I'm interested in this USA-Philippines through the Pacific, so I was interested in that geography. The geography informed the method.”

In the National Gallery Singapore (NGS), the projects talk about worldmaking, featuring artists who reimagine new worlds, think of new ways to bring people together, and new systems of learning about the world. It starts with a survey of works by Filipino-American artist Carlos Villa, whose projects have often tackled, questioned, and addressed the common notions of ‘multiculturalism.’

A widely referenced article written by Preston Fletcher says that while Villa’s career was founded on attempting to make sense of his heritage (“a complexity of Filipino traditions with its layered strains of Asian, African, Indian, and Oceanic cultures”), he was able to produce a personal anthropology that not only follows his own history but also of the larger “dynamics of true intercultural weaving.”

Carlos Villa, Painted Cloak (1971-1972). Photo courtesy of Singapore Art Museum

Villa, who was born in the U.S. to immigrant parents, was a cultural worker, an activist, a teacher, and an artist. “He organized artists of color, women, migrants, within the diaspora in California at that time,” Flores explains. “He was quite influential in prefiguring this different constellation of an art world beyond the mainstream, North American context.”

Flores wanted to begin with Villa, showing 14 of his works, precisely because of the artist’s desire to propose a different social world through his art. He was part of the abstract expressionist movement — even establishing a website that contains interviews and works of other abstract artists, such as Susan Kelk-Cervantes, Deborah Remington, and Dewey Crumpler — but he was also rethinking what abstract expressionism meant in America at that time.

Resonating with this aesthetic is Alfonso Ossorio, another Filipino-American artist who is best known for his abstract expressionist paintings and his sculptural “Congregations” series, the latter being the ones displayed at the NGS.

Ossorio’s work was first exhibited in the Philippines at León Gallery in February 2016. A survey of Ossorio’s work soon followed at Ayala Museum from February to June 2018, and his art was also up for bidding at Salcedo Auctions on February of that same year, with an estimated value of ₱3,500,000 to ₱3,800,000. While he may be belatedly recognized in the Philippines, he was long situated as a significant artist in the narrative of abstract expressionism in America.

Now, eight of Ossorio’s works under “Congregations” have been reactivated in the context of the Singapore Biennale. His “assemblages” — which he reportedly refused to call as such, using the word “congregation” instead — are fantastical objects and entities, such as driftwood and rhinestone, that complete one whole piece. In this reactivation, the biennale makes good of what Flores wrote about the festival’s ‘ethical imperative’: “to remap the world through the circulation of art, creating another geography through the art world and another art world through geography.”

Alfonso Ossorio, Mirror Point (1960). Photo courtesy of Singapore Art Museum

Non-Filipino artists dealing with the Filipino, the Philippines

In keeping with the mission to relearn or unlearn systems of doing, Flores also invited Céline Condorelli, a French artist based in the UK, to host archives in NGS. The artist created polka dotted lounge chairs, inviting guests to rest and take a break while they experience archives. “Archives have to be presented in a different way,” Flores explains. “I didn't want an academic presentation because then there's no pleasure in handling the material.”

The exhibit, titled “Spatial Compositions 13,” enabled Condorelli to break the barrier between leisure and contemplation, to make it known that one doesn’t have to be serious when looking at archives; that there can be joy in it. The lounge set-up created a relaxed, almost domestic atmosphere that does transform archives into less intimidating, more accessible works.

However, Condorelli admits she was hesitant to work with the archives of Filipino artist Raymundo Albano, Filipino artist Judy Sibayan, Fil-Am artist Carlos Villa, Malaysian artist Ismail Zain and Korean artist Ha Bik Chuen — all of whom she was not familiar with prior to agreeing to do the project.

“It is a weird position for an artist to have, to decide to speak about something that you know nothing about,” she says. “But then I thought I can provide a platform for these incredible work to exist.”

Condorelli, an architect and a curator, says she feels the most kinship to these artists, being people who took institutional positions as well as continuing their own practice, and in such a way, making their own conditions for life and work possible. Albano was a critic, an artist, a curator; Sibayan is an artist, editor, and publisher; Villa was a community organizer, artist, teacher; Zain was an artist, lecturer, and cultural worker; and Chuen was a sculptor, photographer, and painter.

“[They were] working on both ends of the spectrum, taking different roles when that was needed — becoming a teacher, a graphic designer, a writer, or an artist or an exhibition designer, depending on what was needed and I can really relate to that position,” she says.

Raymundo Albano, Aleator (1974-1981), as part of Spatial Compositions 13. Photo courtesy of Singapore Art Museum

She is also not the only artist who presented work that was inspired or speaks clearly to history, tradition, or culture that is not one’s own. Turkish artist Hera Büyüktaşçıyan’s “Seldom Seen, Soon Forgotten,” also in NGS, showcased a site-specific installation influenced by capiz shell windows and the binakol textile in the Philippines.

Büyüktaşçıyan, who did her 2018 residency at Bellas Artes Projects in Bataan, explained: “the abstraction of capiz shells question the ability to see or to remain virtually blind towards social and political aspects of everyday life and the cyclic repetition of history. The illusion created by the whirlwinds of history causes a sense of blindness where the image disappears until it is forgotten.”

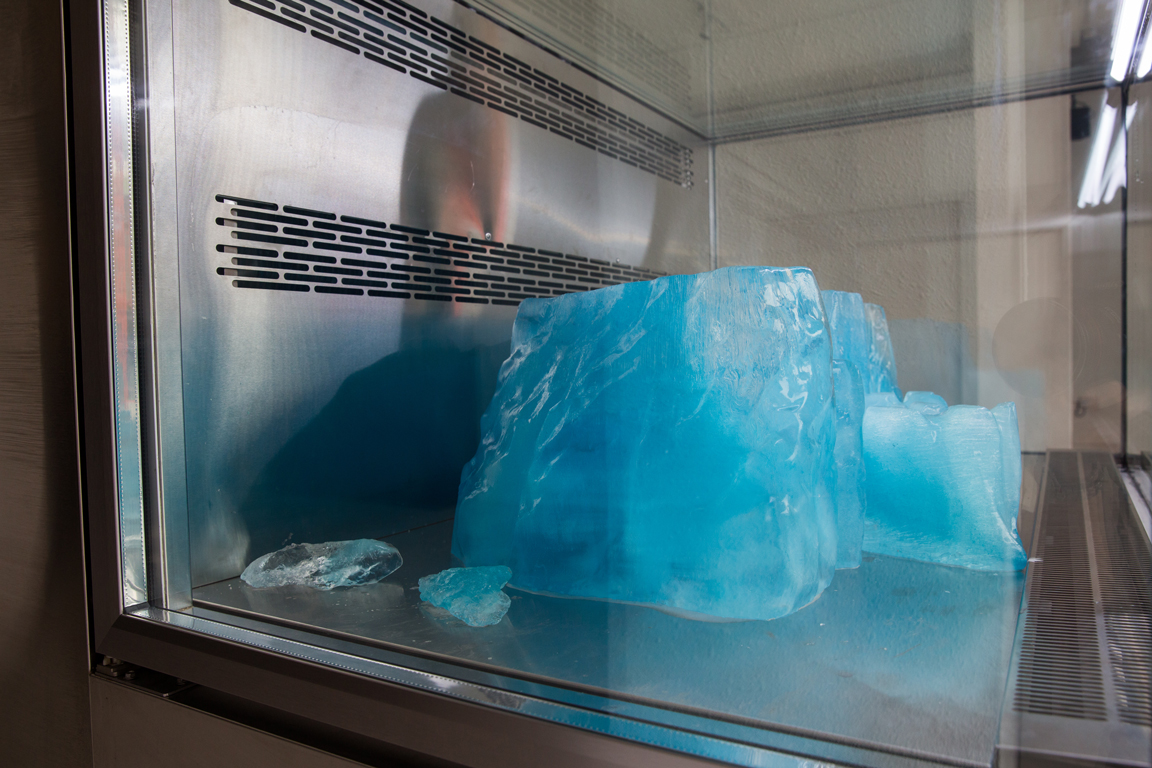

Like Büyüktaşçıyan, Chinest artist Hu Yun also did a residency in the Philippines (at 1335 Mabini), and his work at the Gillman Barracks also explores the nature of history while also interacting with distinctly Filipino tradition. Titled “Carving Water, Melting Stones,” the exhibit reflects on his visits in Paete, a municipality in Laguna, Philippines, known for their woodcarving practice.

Yun first encountered original 1980s dioramas of the National Museum of Singapore at Elias Park Primary School in Singapore, and found that the makers of these dioramas were from Paete. As he revisited the woodcarvers in Paete, he also learned of the situation they were in — that there was a declining interest in wood carving, forcing most of these Filipino workers to find jobs in cruise ships as ice carvers.

For the biennale, Yun then had a Filipino wood carver help him form a diorama, using ice, of a present-day Singapore, as imagined by the students from Elias Park Primary School. Through this almost cyclical conversation between stories and histories, Yun presented history as a form of back and forth dialogue, one that is not always linear, but perhaps zigs or zags or circles.

Hu Yun, Carving Water, Melting Stones (2019). Photo courtesy of Singapore Art Museum

Activating Filipino art

What Flores has continuously emphasized in his opening speech, in interviews, in his quick conversations with guests, is that this year’s biennale encourages participation; that the “public is central in this effort.”

At LASALLE College of the Arts — the only tertiary institution in the world to offer a Master’s programme in Asian Art Histories — the school hosts works that are aimed at having an audience intervene. There is Filipino artist Gary-Ross Pastrana’s “Properties,” which displays static objects used in a play staged in Manila called “Cleansed.” These objects would then be ‘activated’ by performance artists in Singapore; the objects thus taking in new meanings and identities.

Meanwhile, Filipino-American artist Miljohn Ruperto’s “Geomancies” center around an experimental documentary film that explores the relationship between humans and nature, a nod to Flores’ mission of placing LASALLE in the “context of constant learning and engaged investigation.”

“The Mamitua Saber Project” also speaks to this ‘activation’ as a paracuratorial project. According to Simon Sheikh, a researcher and lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London, paracuratorial projects present ideas outside the norm of exhibition-making. He argued that “paracuratorial is a critical response to the marketization of contemporary art and rejection of spectacle, bigness, and the art world credo of ‘the show must go on’ regardless. It is in this sense the anti-biennale or the anti-art fair.”

The Saber project is overwhelming; not because of its aesthetic spectacle but of the wealth of research, text, and information. Filipino curator Renan Laru-an chose three artistic projects to work around the ideas and theories of Mamitua Saber, a sociologist and cultural worker who was instrumental in the development of the civic and cultural life in Mindanao.

“[The project] introduces a curatorial history in Southeast Asia because [Saber] established a museum in 1961 and then formally 1963, which is years before CCP and all other museums in Manila were built,” explains Laru-an. “The museum was built with an endowment from Prince Karim Aga Khan IV, which really locates Mindanao as an internationalist, and that it has its capacity to purchase internationalism.”

Saber, born in Marawi, was also known for his perspectives on politics and culture, which gave emphasis on marginal leadership. Laru-an says he wanted to work with artists and collectives that were research-oriented and who also spoke to this notion of the ‘marginal leader.’ Mark Sanchez, a Filipino artist who worked under this paracuratorial project, centered his installation, titled “From Where Labor Blooms,” on the peasant leader, including videos of his interviews with peasant activist Angie Ipong and former chairman of the Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas Ka Paeng Mariano.

Mark Sanchez, From Where Labor Blooms (2019), as part of The Mamitua Saber Project. Photo courtesy of Singapore Art Museum

“The work deals with the problem of agriculture and the peasant sector in the Philippines and it is the root cause of the biggest problems that happens in the country,” Sanchez explains. “Mindanao is a very fertile island and there are a lot of mining prospects there and what happens is that people, farmers, IPs, they mostly get displaced because of interests in the plantations.”

An entire corner in LASALLE is filled with texts, images, newspaper clippings, documents, photos, and illustrations that Sanchez accumulated from his past works as well as during his preparation for this year’s biennale — which all formed an installation that resembled a diagram of the semi-colonial and semi-feudal structure that still persists in the country and how it trickles down to the conflicts, subjugation, and the decline of agriculture and the peasantry.

The right direction

The six curators that Flores worked with are all under 40, a fact that Flores highlights time and again. “I want the millennial perspective. I believe that the young curators should curate the biennale of their time and they should not wait to be old, senior curators to be given the opportunity,” says Flores.

“I curate differently from them because I came from a different time and I was also trained differently,” he adds. “My curatorial work came out from my work as an art historian, so it was an extension of my art historical work but they have a different history of curatorial practice.”

It is then not surprising that the biennale generally seem to reflect on the anxieties of this generation and how artists are perhaps living within the increasing tensions in the world. In a Financial Times article, social and economic theorist Jeremy Rifkin explained that this generation has a different sensibility from its predecessors. He said, “If you are a World War II baby like me, you see power as a pyramid, very vertical and exercised from the top down. The millennials have a very different idea. They judge a government or party by its institutional behavior.”

He added that ideas around freedom also vary. “My generation defines it as being autonomous, not beholden to others, and values exclusivity,” he explained. “Young people are all about inclusivity, access to networks, transparency. Further autonomy is death.”

This year’s biennale has focused, consciously or unconsciously, on artistic practices that are placed in the conditions of larger histories, larger communities, larger narratives, larger movements than the self, the autonomy. It also recognizes that for contemporary art to make sense to a wider public, it has to speak about or respond to the present state of the world. This is realized in the biennale’s initiatives that extend beyond the walls of galleries, through collaborations with on-the-ground communities in film, theater, and heritage.

Singapore Biennale 2019 invites everyone, as Flores wrote, “to stake a claim on what is right for the world with all its woes and promise” and it “abides by the agency of each one of us to make every step, whether mincing or bold, matter. ” Indeed, “Every Step in the Right Direction” is not a theme; it’s a cry for action.

Cover image: Miljohn Ruperto, Geomancies (2007-2017). Photo courtesy of Singapore Art Museum

Story re-produced and courtesy of CNN Philippines. Access the original here.