By Valerie Ang, MA Creative Writing (Class of 2021)

Darryl Whetter is a writer, editor and inaugural director of the first taught creative writing MA in Singapore and Southeast Asia at LASALLE College of the Arts. His climate-crisis novel Our Sands, published by Penguin Random House SEA (Southeast Asia), will be launched on March 27 2020.

As a student in Dr Whetter’s programme and now one of his thesis supervisees, I have had the pleasure — and sometimes, the terror — of learning from him first-hand the finer points of fiction-making, while I work on my own novel. In this interview, I pick his brain about his latest novel, his writing process, and what goes into the telling of a story.

When people ask you the world’s most annoying question — “what’s the book about?” — how do you respond?

Our Sands is a novel of eco-terrorism and bike-courier love. That’s the elevator pitch. If they seem to await more, I might add that it examines the world’s largest and least sustainable industrial project in the world, the Canadian tar sands, to consider what scientists call ‘the Sixth Extinction,’ the looming mass-extinction of plants, animals and, in all probability, hundreds of millions of impoverished coastal humans. It’s also a family novel, though, because climate-change is going to affect everything: the state, the family, global politics, even romance.

An open-pit mine in Canada’s tar sands. Photo: Dr Darryl Whetter

An open-pit mine in Canada’s tar sands. Photo: Dr Darryl Whetter

Sands is set in Alberta, Canada, nearly 13,000 kilometres from Singapore, where you now live and work. Has that distance (literal and figurative) helped or hindered your telling of this story?

Helped it, definitely. I’ve always loved Salman Rushdie’s phrase ‘imaginary homelands’ for that way we fiction writers slip off the actual map into an imaginary one. My only sibling and my wife both did their graduate degrees abroad, whereas I hadn’t lived outside Canada until these last four years — half of the writing time for Our Sands.

I have a very uneasy relationship with nationalism, but I did feel undeniably proud of Canada while living here for its/our trailblazing work with same-sex marriage and, more recently, trans rights. I have also, though, brought my national shame to an acute boil in this novel. I’ve loathed ‘our’ tar sands all my adult life, but nothing opens up the complexities of an issue like writing about it.

Speaking of writing about issues, I noticed you also tackled the energy crisis and other ecological concerns in your 2012 poetry collection Origins.

Good eye (and ear). Yes, I am revisiting some subjects — namely energy and extinction — from my first poetry collection here in my third novel. That’s primarily a function of the scope and significance of those issues. To do even moderately serious reading on evolutionary theory is to meet one of those rare subjects that just keeps blooming and blooming.

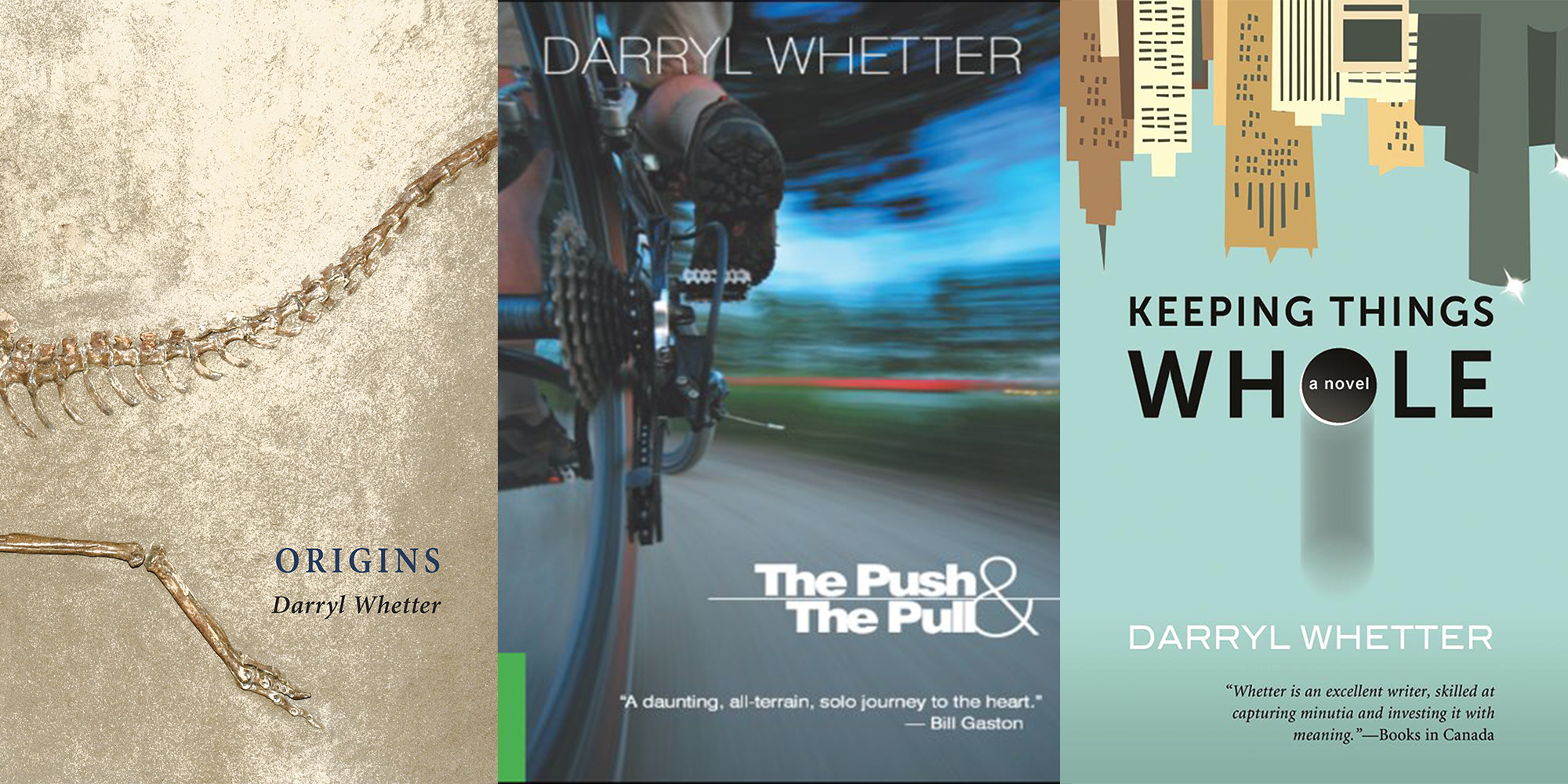

My first two novels, The Push & the Pull and Keeping Things Whole, tackled cycling, contraband and smuggling in Canada. These were fascinating subjects for eight years of writing but once I was done with them, I was done. Thinking about species success, and failure, across changing ecosystems, though — I'm confident that will fascinate me forever.

You’re not only the inaugural director of LASALLE’s MA in Creative Writing programme, but also teach the story and non-fiction modules personally. How has your teaching of the craft informed your own practice of it?

I’ve been a university professor of fiction and poetry for 20 years, and I picked up most of my lessons from students in the first few years of teaching. Teaching others is definitely the most powerful way to learn. The second I began teaching, I recognised all the mistakes I’d made in my own young work, fundamentals like not letting us know a character’s gender or age on the first page. Most of us begin writing to please ourselves; eventually you have to shift to pleasing the reader.

That all said, I hadn’t taught creative non-fiction at the graduate level before arriving here to LASALLE. This past year I’ve released two creative ‘side-car’ essays related to the novel, one in a more academic journal, Oxford University Press’s ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment and one in this month’s The Brooklyn Rail out of New York. I love, love, love novels, but I don’t think we have to regard them as hermetically sealed off from everything else. I’m thrilled to write these parallel texts of creative non-fiction.

Conversely: is there anything you’ve learnt from your students here in Singapore that went into the writing of the book?

At the level of craft, yes. My best students inspire me the same way reading great new novels from around the world inspires me. I think, ‘Wow’ and ‘Thank you’ and ‘I gotta keep my game up.’ Some schools have science departments and applied science departments, aka engineering. I often think of literature as applied philosophy or applied psychology. Great student writing is great writing: it teaches me what it’s like to live in the world, who people are and how they tick.

On a more personal note, my novel considers purposefully living child-free. Most of our graduate writing students are older, and several have children. I thought about their children, and the other students who wonder if they will have children, while I read harrowing research like David Wallace-Wells’s The Uninhabitable Earth. Considering their perspectives went a long way towards broadening my own.

Any future projects you’d like to talk about? What are you working on now besides, presumably, grading our essays?

I admit to the terror of not having another novel idea right now. I started Our Sands shortly before my second novel came out and my second shortly before my first came out. For the first time this century, the neutral gear of my brain doesn’t have a novel to think of.

That said, I have plenty on my plate — what I should be working on at the moment is the screenplay draft of Our Sands I started but had to set aside during my grading crunch. I’m hoping to work with a Canadian filmmaker I know who’d be perfect to direct Our Sands as a dramatic feature. I’m also working on a few short pieces of creative non-fiction; little vacations after the novel. On top of that, I’m shopping around my first memoir, and that would need a rewrite if it’s picked up.

I can’t help but cheekily echo the famous refrain from your story workshops: did you read your work aloud?

Religiously! In any class I teach, whether it’s a short afternoon workshop for the Singapore Book Council, or one of the Creative Writing Short Courses I designed at LASALLE for community learners or the graduate writing workshops, I promise every student that the single most effective technique for improving their writing is to read it aloud. The more someone thinks not reading their work aloud isn’t for them, the more they need to do it. Nothing helps you proofread better, and that’s the most superficial gain. You’ll also spot repeated words, clunky phrases, verbose dialogue and anywhere you’re not making sense.

If you want to be a better writer, you must read your work aloud. Period.

Our Sands will be launched at LASALLE College of the Arts on Friday 27 March, and can be purchased at Kinokuniya as well as other local bookstores. Dr Darryl Whetter is also scheduled to read from the novel at the 2020 Ubud Writers and Readers Festival in Bali.