As the COVID-19 pandemic shut down physical theatres and performers and theatre makers shifted online out of necessity, the shift online opened up new possibilities for more cross-border collaborations. School of Dance & Theatre lecturer Dr Felipe Cervera, together with fellow researchers Kyoko Iwaki and Kristof van Baarle from the University of Antwerp (UAntwerp), conceived an ambitious vision: what if students from LASALLE and UAntwerp worked together across continents and timezones?

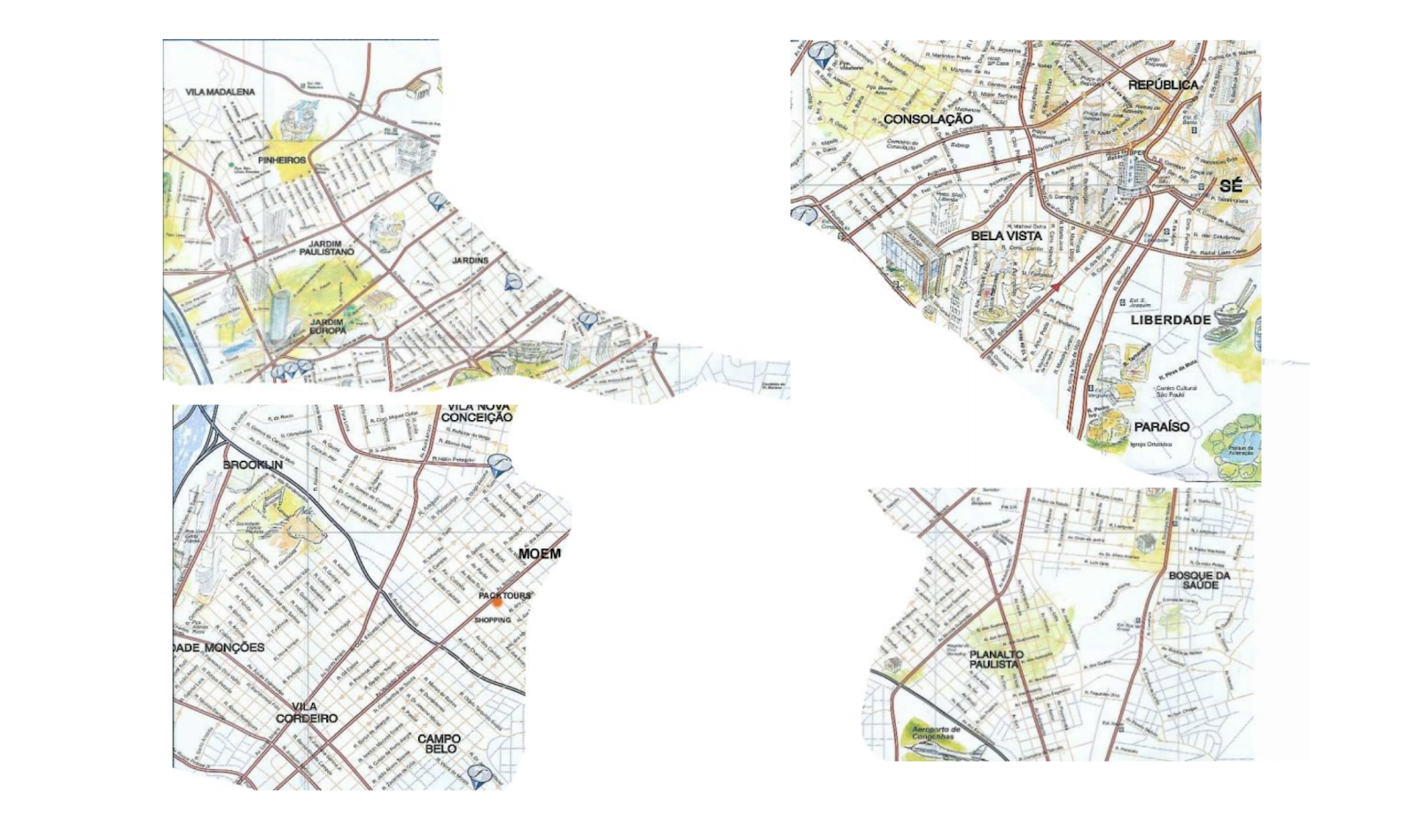

Over five weeks, students from LASALLE and UAntwerp explored the emerging dramaturgies of space in performance, culminating in a proposal for a site-specific performance in São Paolo, Brazil. This COIL (Collaborative Online International Learning) module was specially created for current global circumstances, Felipe shares.

“Public spaces and digital space have been radically reconfigured as a result of the pandemic. The current generation of performers and theatre-makers will have to reckon with how they can recover public spaces with performance, as well as how the digital space has become a new public square where all communities can come together and connect,” says Felipe.

At the end of the experience four participants – Sofie Binte Shahrin Buligis and Patrick Alvarez from LASALLE’s BA(Hons) Musical Theatre and BA(Hons) Acting programme as well as Thomas Nijskens and Atalya De Cock from UAntwerp’s Theatre, Film and Literature Studies programme – came together for a short discussion about their experiences on the project. Moderated by Felipe, the conversation was a microcosm of the peculiarities of working together during the pandemic. Dialing in from three different time zones, time flattened as morning, noon and night all co-existed in an ephemeral digital meeting room.

How was your experience of COIL, both individually and collectively?

Patrick: The biggest thing that struck me was how challenging the collaborative process was, when working online for the process of conceptualising performance. When you devise in a physical space, there is a ‘Yes, and…’-type of process where we build on everyone’s suggestions. But working online, the process can feel more outcome-driven and it's harder to establish rapport, so sometimes suggestions would be turned down immediately or decisions would be made by some and not others, so it wasn’t as collaborative as it potentially could have been.

Atalya: Yeah, I do agree with that, especially because it's not only online, it was also such a big group – six or seven people – which made it difficult for everyone to chime in equally and agree on the concept, so it took a long time to get going. As I would sometimes lead the conversations in our group, I learnt to be more assertive and confident in speaking up – because everyone is here to collaborate and you’re shielded from others by a screen. [laughs]

Sofie: I feel that our group had a pretty collaborative experience together. We had a lot in common, despite the fact that we all came from different places. A lot of us are queer or a racial minority, we all loved music and had a background in the arts, and these really helped us to find common ground. We were generous in sharing our experiences of the pandemic and it set the tone for the rest of the collaboration.

Thomas: We definitely were lucky in that our personalities were compatible. I made friends through this project and it was very interesting to learn about the political situation and culture in our countries. Of course you had a couple of people who will tend to hang back a bit more – like Atalya said – but in smaller groups you’re forced to speak up more and I think that’s typical of all group dynamics.

How did you arrive at your final proposals?

Sofie: For my group, a lot of us had experienced discrimination, so equality was a huge theme in our project. We wanted to make sure that the performance that we put up wouldn't just be for people with higher socio-economic status, which is often the case for a lot of theatre works. Especially with the emergence of digital theatre, even though a lot of content is made accessible online, people take for granted that everybody has access to a laptop or an internet connection. That’s why our project had mixed dramaturgy – we had some performances that were happening in the actual spaces and some that were happening online. Audiences could then choose what most accessible for them.

Thomas: Our group also realised that although we can talk with each other and technology makes the distance between us feel much smaller, there are still a lot of big differences that get overlooked when we make generalisations. So when we researched and talked about Brazil, we felt a false familiarity with the locale, but also realised that our perspectives were coloured by our European or Asian contexts. The semblance of closeness does not really translate into concretely knowing the Brazilian experience. We were careful not to go beyond what our limited knowledge could afford us when it came to the experience of local Brazilians.

Atalya: Our group also talked a lot about how our project fits into Brazil or whether we are overstepping boundaries. Our initial chosen location was an old prison in São Paolo because we had these ideas about having this parallel between a prison and our experience of isolation during the pandemic. But the more we thought about it, the more we realised we were appropriating these people's experiences. There was a lot of history behind that building as well, such as a massacre that happened there, so it would not have been appropriate for us to use it. In the end, instead of isolation, we made it about connection and celebrating freedom.

Patrick: The common thread between our final project and the context of the pandemic is how people can connect worldwide. Humans are social creatures who seek to communicate. Our project proposed live streaming from São Paolo, Brazil, letting anyone anywhere in the world join in as long as they have a working device and an internet connection. That said, one thing I did wish we incorporated was also the difficulty of said connection. Sometimes on Zoom, there will be moments when the connection lags, or people speak over each other, inhibiting flow. It might have been interesting for the project to mirror real life difficulties as well.

How did the experience change or impact your sense of self or practice, as an artist, a performer or theatre maker?

Sofie: This project definitely made me more aware of the role I play in a group setting, regardless of whether it's an online project or face-to-face.

Thomas: Yeah, I had the same experience on the project. It confirmed what my strong suits were and what qualities were lacking for me as a group member or a professional. I learnt that I was too focused on being conceptual and generating ideas instead of noting things down and doing my research. So I really started changing and being very conscious about that.

Atalya: I think it was also interesting because I feel like our programme in UAntwerp is very theoretical most of the time and we rarely put theory into practice. So it was nice to have this very different way of approaching academics and theories about theatre and collaborate on something more creative and practical. It helps with making a portfolio and knowing where to start with projects like this.

Patrick: My biggest takeaway was the concepts we learnt from the lectures by Felipe, Kyoko and Kristof, especially Lefebvre’s theory of social spaces. I’ve noticed some of these concepts coming into play in my practice.

Sofie: For me it made me reflect that in Singapore, a majority of the people in the arts are women. So I’ve become used to women-centric spaces and during this project I was hyper aware of how I needed to assert myself to make my voice heard. But I emerged from it with a stronger sense of self, in the way I carry myself and own my ideas, my purpose and my style of working. And while it’s not always easy to have good conversations online, by creating an entire project over Zoom, the COIL project has helped to assure me that as an artist, I have the confidence to keep creating whatever the circumstances.

Patrick: Yeah, the project itself did a very good job showing us how limiting our earlier perspectives were, not just as students but as creatives, collaborators and thinkers. It opened up a new realm of online collaboration and I hope more students get to experience this.

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.