In conversation with: Nerissa Arviana Prawiro on her TechWomen 100 win and her evolving approach to user-centred design

Product Design alumna Nerissa Arviana Prawiro is no stranger to using her design skills for social good.

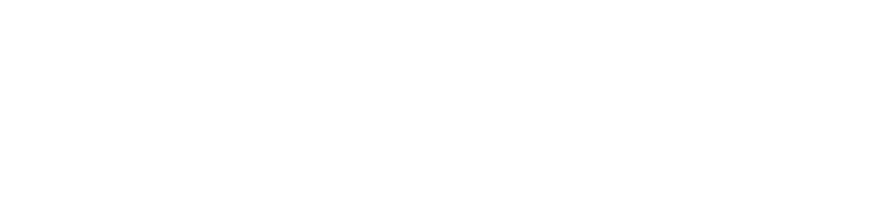

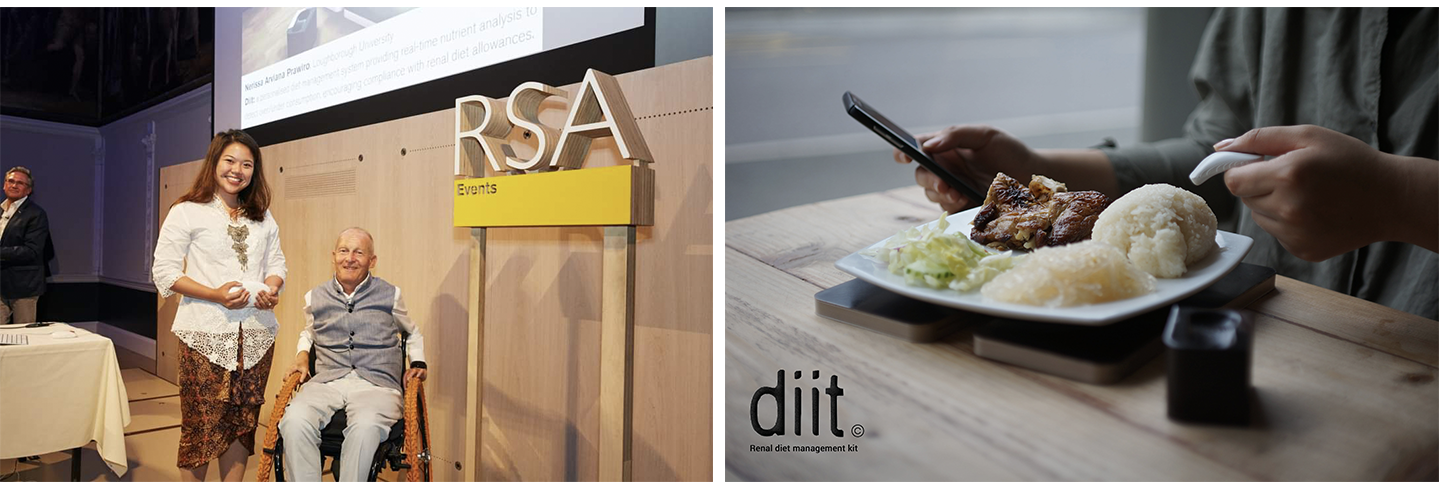

In 2014 during her final year of diploma studies at LASALLE, she earned a Red Dot Concept Design Award for Freund, a wearable technological device that dampens the wrist tremors felt by those with Parkinson’s disease. After graduation in 2017, Nerissa also won the Royal Society of Arts (RSA) Student Design Award, for a smart renal diet kit that helps chronic kidney disease sufferers adhere to their prescribed micro/macro nutrients intake. She is now a Fellow of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (FRSA), a prestigious award granted to individuals that the RSA judges deemed to have made outstanding achievements to social progress and development.

Nerissa’s human-centred design ethos recently helped her to clinch yet another accolade in 2020. Currently working at Goldman Sachs in London, UK, as a user experience designer, she received the TechWomen100 award, which recognises and celebrates the achievements of women working in technology.

We spoke to Nerissa about her recent win, her crossover into the financial sector and pivot from product design to UX design as well as how the highs and lows of her LASALLE education has helped her design practice to mature and evolve over the years.

You’re currently working in a field that is not typically associated with design. What led you to make the leap?

To be completely honest, I didn’t know much about finance when I first applied for the role. I saw it as an opportunity to challenge myself to step out of my comfort zone and grow as a designer. I’m very proud that I made that leap, as it has unexpectedly broadened my horizons and skill sets as a designer.

Of course, when your project stakeholders are traders and/or computer scientists, it can often trigger insecurities about not knowing enough about business contexts or programming concepts. But I always remind myself of the advice I once received from a mentor at work, “Don’t worry about not knowing everything about finance or the world of securities – you studied design, not finance. You just need to know enough for you to be able to empathise with the user on the problems they’re facing. Regardless of the business, treat issues as any other design brief and approach it using the foundation you know best: design thinking.”

How have your design fundamentals helped you?

I draw on my foundation in design thinking constantly and design thinking has increasingly become widely accepted as a business problem-solving tool in the industry. In my experience, applying this creative thinking process early on with end users, clients and project stakeholders has helped me to adapt faster to unfamiliar design challenges. This user-centred approach also enables better understanding of problems and ultimately a more ‘human’ design solution.

The innovative problem-solving skills I’ve learnt have also helped ease the transition from product design to UX design. This is not to say that there wasn’t a period of adaptation and familiarisation. Being trained as an industrial designer, I was used to thinking in 3D and ideating via the sensory play of form, material, texture and finishing. When I first began digital UX design, it was difficult for me to think creatively without tangible stimuli. Also, the design constraints and challenges for UX design are different from the typical manufacturing limitations that we have to consider for product design.

But over time, I’ve realised that the design process and skills are the same regardless of whether design briefs are tangible or digital. Trusting in the process, being unafraid of asking questions and, ultimately, perseverance, have helped tremendously in easing the transition.

Nerissa attending the Royal Society of Arts (RSA) Student Design Awards ceremony in 2017 (left); a concept image for diit, the smart renal diet kit designed by Nerissa (right).

How has your conception of designing for social good evolved over the years?

One of the biggest differences I see in my growth as a designer is that I’ve come to understand that innovation doesn’t only refer to ground-breaking, fancy technology – instead, the focus should be on solving a user’s unmet need. This could be as simple as redesigning how a timer dial looks like on a sandwich maker to make it more intuitive for users in last mile communities to understand and adapt to. So while in the past, I would first conduct market research on the latest technological inventions and focus on the function and technical details of a product, I’ve now learnt how important it is to empathise with the users first, digging into what exactly that unmet need is before thinking about the solution.

I’ve also learnt how powerful collaborating with users can be. This is something that I understood in theory whilst I was a student but only fully appreciated and put into action in recent years. Being able to collaborate with end users during the design and testing process enables innovation and validates the commercial viability of the design. This is a key part of building good designs.

Most importantly, I’ve realised that design for social good doesn’t only revolve around the tangible/digital product outputs. It starts from helping users understand that design is a way of life, introducing design thinking as a problem-solving tool to help empower businesses and individuals to solve their everyday problems.

Nerissa delivering a keynote speech on ‘Using design thinking to manage your career’ during the London Job Show 2020.

Currently you lead a university outreach programme. What are the skills, mindsets or perspectives that you think are important for a design student today?

A common error that I often see in portfolios and/or during interviews is when designers spend too much time creating glossy renderings of their products. Another is when they spend too much of their energy explaining what methodologies and tools they used, instead of using their time to explain their design intents, why they took a certain path or why they made the decisions they made.

My tip would be to focus on the ‘why’ of things rather than the things themselves – in other words, to focus our energy on intentionality and the aspects that make great designs ‘human’, such as accessibility, usability and inclusion.

What are the greatest takeaways from your time as a student that has left a lasting impact on your design practice/ethos?

As cliché as it may sound, determination, perseverance and resilience were the key takeaways from my time at LASALLE. There were countless times where I hit a creative wall whilst designing a product, when the rush towards submissions became overwhelming, or when I tried my best but the outcome did not meet my expectations.

There were many incidents that made me question my passion and motivation in pursuing design as a career choice. Going through such pivotal moments, when it was tempting to just give up, taught me invaluable lessons about self-discipline and perseverance. These moments have helped shape the person and designer I have become. Till today, whatever the challenge, I remind myself of those moments when I wanted to give up but decided to keep pushing on.

Another valuable lesson that I learnt during my years in LASALLE is to be gentle with my assessment of my work and myself. More often than not, the saying that ‘we are our own worst critics’ is especially relatable for designers – knowing that everything requires process and practice is something and being patient with myself are habits that I’m continuously practising till today.

Freund, Nerissa’s Red Dot Design Award winning work that helps reduce the wrist tremors felt by those with Parkinson’s disease.