Art therapy as ethical business of change: Conversation with Emylia Safian

Art therapy as a profession began in the 1900s in Europe and the United States. Hospitals and individuals tapped on art therapy for psychological conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and cognitive impairment. While the practice gained recognition as a valid form of treatment, professional organisations began to form. They include the American Art Therapy Association, founded in 1969, and the Australian, New Zealand and Asian Creative Arts Therapies Association (ANZACATA), which opened its membership to Singapore graduates in 2009 and supports training programmes across Asia. Both associations promote art therapy as a regulated mental health profession.

To learn more about the discipline in Singapore, I speak with Emylia Safian, Lecturer, MA Art Therapy, LASALLE College of the Arts. We chat about resonances and differences between art therapy and fine art, making the practice relevant in the era of climate change, challenges and insights from being in the field, and more.

You graduated with a BA in Psychology and Humanities from Monash University and an MA in Art Therapy from LASALLE, where you currently teach. How would you describe your journey with art therapy from your schooling days till now?

It has been 15 years since I graduated from LASALLE. I was part of the first cohort way back in 2007, two years after the school had the vision to establish the programme. Back then, art therapy as a professional discipline was relatively unheard of. I only knew about it through a short training programme conducted by a community service agency in Singapore facilitated by a psychologist. Through that, I initially understood art therapy to be diagnostic and predominantly used as an assessment tool. But my big question was centred around its healing aspects. When talking about art therapy, I also want to hear about it as an intervention, and how it helps heal through the traumas and the challenges in life.

The biggest challenge was to understand what art therapy as a professional discipline is all about at a time when no one else in Singapore fully understood how art heals outside of artistic fields and industries. I think artists inherently know that art can be healing for themselves, but this is less obvious in psychology, counselling, and social work. So that was a challenge.

The environment in LASALLE must have been very different from other colleges at the time. Did you create art then?

I would not say I had an art practice, but I liked making crafts and three-dimensional objects. Coming into an arts college opened my mind, heart, and eyes to embrace what an art practice is all about. Through the experiential modes of teaching, I could experiment with different artistic mediums. The art therapy field is a marriage between psychology and the arts, so I think it would be different if I were to study art therapy in a social science department.

At LASALLE, art therapy students are required to create reflective visual responses. In 2018, you also worked on ‘Traces’, an exhibition where art therapy trainees created artwork based on their interactions with children living with adversity. Why is it important for therapists to engage in the personal process of creating art?

The root of ‘aesthetics’ is the Greek word aisthetikos, which means sense perception. This perception of the senses is a fundamental aspect of art therapy. For instance, we could be working with individuals who have a limited verbal capacity due to illness, developmental differences or even trauma. The art therapist who is fluent in material language will be most comfortable working beyond words.

In a way, we bypass the cognitive and the intellectual to work at the level of the senses. We are talking about working in a very intimate manner, and this intimacy creates trust. Art therapy is not merely about working with the art medium. It is about making art in the presence of the art therapist. Here, the art therapist becomes a witness, a helping hand, or sometimes makes art on behalf of the clients and patients. The healing takes place through the therapist’s gaze, and the relationship can be seen as a healing vessel.

And so, yes, it is essential for art therapists ourselves to have a personal relationship with our own art-making. Whether our works are exhibited or not, the artistic process allows us to be in touch and in tune with this notion of sense perception.

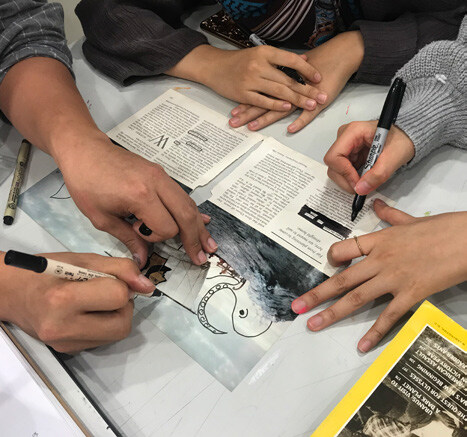

Group training of art therapy trainees in collaboration with the School of Dance & Theatre at LASALLE. Image courtesy of Emylia Safian.

Art therapy trainee installing artwork for exhibition ‘Traces’ in 2018. Image courtesy of Emylia Safian.

You mentioned that art therapists would sometimes make artworks on behalf of the client. Could you share more about that?

It is a practice that is quite common in palliative care settings. Often, clients may be fully medicated and not have the ability or energy to make something. In these debilitating situations, the therapist makes and engages with the client. It is not just about the individual creating something. We also tap on imagination, which comes before the making. Making art on behalf of the client taps on getting into that imaginative space together.

In 2018, you worked with artist Yanyun Chen on a workshop, ‘Conversation with your Scar’ at the Singapore Art Museum (SAM), where participants penned a letter to their bodily scars. What differing roles that you and Yanyun have in that session?

The workshop was ideated surrounding Yanyun’s exhibition, ‘The Scars that Write Us’, which was part of the President’s Young Talents show and won the People’s Choice Award. SAM connected us, and I did not know Yanyun personally before then. Because her works are very personal, we wanted to achieve a certain level of intimacy with the participants. My role then was to maintain a sense of psychological safety. We all project a part of ourselves onto artworks created by others. But when we intentionally invite an audience to tap into the personal realm, we also invite many emotions into the room. There has to be some kind of deliberation and consideration of how we can make it as safe as possible for everyone. The workshop was not intended to be a therapy session. It was an experience to engage with Yanyun’s artworks and use them as a source of inspiration for looking into our scars and drawing strength from them.

The people in the workshop probably did not know each other, and they must have felt vulnerable to explore very personal experiences in a public area. Therapy sessions mostly happen in a private clinical context. What are your thoughts on an art museum being a therapeutic space?

‘Traces’ was a project funded by The Ireland Funds Singapore in 2018. The inspiration came out of multiple visits to Imaginarium. For those visits, we collaborated with SAM to host children from child protection services residing in various care settings and shelters to the museum during the school holidays not only to view but to also make art. We were acknowledging the museum as a place for critical thinking and looking at how we can use the artworks of others as part of the art therapy process.

But going back to what makes a therapeutic space, my thoughts lean towards how it is not just about that physical building, room or even a particular environment. It is about psychological interiority. The external space connects with this inner world in fascinating and often unexpected ways. So what is therapeutic or otherwise is highly subjective. It depends on the individual’s lived experience of our time and place.

We talk a lot about attachment theory in art therapy, but there is also a sense of place attachment: how one connects with a particular space or how emotional bonds between persons and place are developed. The art therapist can then facilitate this place attachment to a space like a museum, community centre or even a park. The sessions do not necessarily happen behind closed doors because sometimes that could be triggering for clients.

Visit to exhibition ‘Imaginarium 2018: Into the Space of Time’ at SAM. Image courtesy of Emylia Safian.

You have also been thinking about how the practice of art therapy will evolve in this era of climate change. Could you tell us more about this?

It is a question that none of us can avoid anymore. We must think about making art therapy relevant in today’s anthropogenic times. Your question brought me back to something that my previous clinical supervisor used to say, which is that art therapy is the business of change.

This is a quote I never fail to share with trainees. It is a very powerful idea because clients come in seeking a change. They are in therapy because maybe they are feeling stuck or distressed. At this particular time, there is just so much ambiguity about the future, and we are only evidencing glimpses of what is to come. This anxiety is pervasive, both consciously and unconsciously. We only start paying attention to it when we sense distress in our bodies or in relationships with others.

The term climate anxiety or eco-anxiety has been used a lot recently. But my big question is: how do we directly link these distressing feelings to climate change? It is also collective. Whether we like it or not, I think we are all influenced and impacted by climate change. In a way, I also feel that climate anxiety should not be pathologised. Should we even distinguish it from other forms of anxiety, which may arise from personal situations? These are big questions I do not have answers for yet, but I am at a stage where I am thinking about how anxiety surfaces in different forms.

If we adopt a psychodynamic perspective, which privileges the non-conscious and the relational, art therapy can offer a holistic take on all dimensions of the human experience, from the sensory to the emotive to the cognitive. When we make something using materials, the sensation of touch brings up certain emotions. When we start to make meaning of it, our rational and cognitive aspects come into the picture.

So, for instance, sometimes a client comes in with psychosomatic symptoms, like unexplained headaches and insomnia. The therapist and the client can together explore that distress using imagination, symbols and play. Experimentation is the language of the psyche. The psyche does not speak in a clear language, so we go back again to the importance of sense perception. As art therapists, we can get the clients to transform overwhelming feelings into more manageable bite-sized pieces.

More and more of my peers also struggle with climate anxiety, where global warming feels almost unsolvable. Art therapists have specialisations in trauma, relationship management and so on. I wonder if eco-anxiety will grow to be an issue of focus in the future?

I do not think it is about specialisation because climate change impacts every one of us. Everything is interwoven. But there is a paradox also because the more we use terms like climate anxiety, the more we attempt to split climate anxiety from other forms of stress. The big question is, should we even separate them? It is a collective feeling, right? It just manifests in different ways.

That is a great point. The media often portrays climate change as separate from our own lives. As an educator, how do you bring an ecological awareness to the guidance of your art therapy students?

Firstly, it is about looking at the materials we use in relation to sustainability. Art therapists do not exhibit clients’ artworks. It is very different from creating for exhibitions in the fine art world. In art therapy, the work is highly confidential. It is for personal meaning making and insight. So, if it is not visible to others and only for ourselves, why do we create and use so much material? Once the client has internalised the artwork, the artwork may not bear as much meaning anymore, right? The product itself is what you have taken in. Thinking about this, the materials we use become very important as we contribute to more and more waste. So, we can start exploring ways to create our own tools. There are a lot of new ideas now to use natural-based plant dyes and make your own clay from the soil.

Secondly, the idea of bringing ecological consciousness is also about incorporating a collaborative attitude into class. In this time of the Anthropocene, or the age of human influence, we have to start examining our relationships with fellow human beings. Ultimately, we are all interconnected and a part of this social network to elicit change. We can start by thinking about what we can contribute to others. For me, everything is quite related to this notion of ecological consciousness.

Sometimes, it is about the logistics of a practice. In the fine art world, people are talking about how to make and exhibit art in more environmentally friendly ways. COVID-19 has highlighted some details, like the consequences of plane trips, artwork transportation and packaging materials. These are nitty-gritty things that are not exactly attractive or fun to problem solve. But the collaborative energy you speak of is what we need to tackle them.

Now people are using fewer paper catalogues and brochures too.

Yes, we see many more QR codes now, which are helpful environmentally but not too accessible for the older audience. Many considerations to weigh!

Besides ecological concerns, what has been the biggest challenge of being an art therapist and or educator in art therapy?

There is a need to balance confidentiality or the introverted traits of art therapy with the exhibitionistic demands of sharing the field with a broader audience. To develop more awareness of the discipline, you need to be louder somehow. I see a big challenge in drawing the right balance. When we exhibit artworks, how do we honour the client? We need to think through what is ethical in each scenario.

On the flip side, what has been the most rewarding in this field?

I recommend a book to all trainees and supervisees. It is called On Learning from the Patient by Patrick Casement. I would like to think of the journey as learning from the clients and the trainees. They are the biggest gifts, and it is a privilege to work alongside them.

Group training of art therapy trainees in collaboration with the School of Dance & Theatre at LASALLE. Image courtesy of Emylia Safian.

Lastly, what are your hopes for art therapy in Singapore?

Ronald P. M.H. Lay, the Programme Leader of the MA Art Therapy Programme at LASALLE recently wrote an article in TODAY titled ‘The case for regulating art therapy in Singapore’. The hope for me, as well, is to get the profession legislated and for our art therapists to be formally registered in Singapore. Doing so would protect the vulnerable persons that we work with. I also hope to see Asian practices emerging from this part of the world. Our indigenous cultural wisdom can become the centre of art therapy in the future. Right now, we understand psychology as a discipline mainly coming from the Western world. Tapping on our indigenous cultures might bring up a lot of other new practices that have not been seen before. So yes, it is more about looking within rather than looking out.

That is all the questions I have. Thank you so much, Emylia. That was very enlightening for me.

The questions helped me reflect deeper and further on the field, so thank you.

This interview originally appeared in CHECK-IN 2022, a publication of Art & Market. Reproduced with permission.